WEBER AND FIELDS

The grandaddy of all two-man vaudeville comedy teams, Weber and Fields are the direct progenitors of Gallagher and Shean, Smith and Dale, the Marx Brothers, and Ted Healy and his Stooges, among countless others. The fact that their influence can be traced to so many (and such diverse) acts gives a strong indication of the complexity of their appeal.

They were both dialect comedians and a knockabout team and so could capture the hearts of the highest and lowest factions of the audience simultaneously. A “Dutch” act, masquerading as two German immigrants, the two would engage in outrageous word play, punctuated with slaps, kicks, punches, eye pokes, and choke holds – massacring the English language at the same time they made mincemeat of each other. Their most frequently quoted exchange went like this:

MIKE: I am delightfulness to meet you.

MYER: Der disgust is all mine.

MIKE: I receividid a letter for mein goil, but I don’t know how to writtenin her back.

MYER: Writtenin her back! Such an edumucation you got it? Writtenin her back! You mean rottenin her back. How can you answer her ven you don’t know how to write?

MIKE: Dot makes no never mind. She don’t know how to read.

The fact that such a category as a “Dutch” comic even existed provides a real window onto another world: the 19th-century, when Germans were a significant faction in New York City, much as Asians, West Indians and Latinos are today. A German subculture once flourished in New York. The popularity of beer and hot dogs are among its lasting legacies, as are the “Katzenjammer Kids”. But two early-twentieth century disasters eviscerated the community and forced it into the woodwork. First, the 1904 burning of the ferryboat General Slocum, in which 1,030 German-American women and children were killed, took the heart out of the community. And then World War I and its jingoism prompted German-Americans to assimilate rather than suffer the bigotry of their new countrymen. If not for these two disasters, Germans might be as visible in New York today as, say, Italians, Russians, Poles or Greeks.

But Weber and Fields were not Germans at all – they were Polish Jews.

Moses Schoenfeld (Lew Fields) and Morris (“Joe”) Weber were both Polish-Jewish immigrants to the U.S., born within six months of each other in 1867. They grew up in the Lower East Side – a densely populated, poverty stricken neighborhood where kids ran the streets in packs. The boys met at age 8, while watching some clog dancers on the playground. The young Fields immediately bragged that he, too, could clog dance – and on a china plate without breaking it. In no time he succeed in ruining much of his mother’s good dinnerware, and received a drubbing for his efforts.

The boys went to school on Allen Street not far from, where 120 years later, vaudeville would once again rear its ugly head (this time with tattoos and body piercings)—at a club known as Surf Reality. The boys were serious students, but not of the required subjects. In every spare minute (and many that were not-so-spare) they practiced the skills that would later help make them famous: tumbling, joking-telling, clog dancing. Like the leading Irish knockabout comedians of the day, Needham and Kelly, and Harry and John Kernel, they put padding under the clothing and practiced smacking each other around for hours on end They practiced falling onto an old mattress.

In the 4th grade they were both expelled from school for their disruptive behavior. From there they worked at odd jobs to make money to pay for theatre tickets.

By age 9 or 10 they had an act. Three acts really, a blackface**, an Irish, and a Dutch, in descending order of their popularity with audiences. Their first public performance was at a local benefit. The boys did an act in blackface, wearing two special matching suits sewn by Lew’s brother. Their mothers even turned out for the event. Everything went wrong in the performance, but the audience was gracious, and so the boys were bitten by the bug.

As Weber and Fields, they begin working some of the ubiquitous Dime Museums in the Bowery and environs. After two weeks at Morris and Hickman’s East Side Museum, they garnered a month at the New York Museum doing Irish and blackface turns. When they heard that the owner of the Globe Museum was seeking a Dutch act, they devised one toot suite. The wininng formula was Lew Field’s brainstorm: a knockabout act but with a “Dutch” accent, instead of an Irish one. To cement the illusion, the two glued on two phony little beards and smeared their faces with whiteface. The fractured dialect was easy – they’d spent their entire lives listening to it.

By 1882, Weber and Fields had been doing a sort of ethnic quickchange act employing Irish, Blackface and Dutch characterizations, up and down the Bowery for four years. They were already making more money than their fathers (which wasn’t much), but they hadn’t yet played Bunnell’s Museum, a step up the ladder at 9th Street and Broadway. In order to get a booking, they told Bunnell, an impresario in the tradition of P.T. Barnum, that they know where he will be able to locate a Chinese man with a third eye in the middle of his forehead, and that they would tell him where he was if he would book them at this museum. Bunnell was duped, but by the time he made the discovery, Weber and Fields have already made a hit at his theatre, so he couldn’t be mad. Part of the act’s appeal in these early years certainly has to have been the fact that the boys were so ridiculously young. The sight of these mismatched boys (Lew was 5’11”, Joe was 5’4”) in heavy padding beating the tar out of each other with machine like rhythm must have been delightful.

The next few years were spent gaining valuable on-the-job experience in small-time theatres in New York and other cities in the Northeast, and very slowly climbing up the pecking order. Time spent in minstrel shows taught them the valuable skill of improvisation, which was to be a keystone of their act.

In 1885, the Adah Richmond Burlesque Company specifically requested a Dutch act, and the boys cooked up a new one, consisting of converted minstrel jokes padded out with knockabout business. This new routine slayed the audience. With all the vigor and enthusiasm of youth, they made every element more extreme than was customary – more and crazier malapropisms and more slapstick mayhem. From here on in Weber and Fields would be “Mike” and “Meyer”, two perpetually arguing German immigrants in loud checked suits and derby hats, whose spats generally arose from their misunderstandings of the peculiarities of the English language, and quickly devolved into punching, kicking slapping, and eye gouging.

Their salaries and their prestige continued to rise throughout the 1880s as they toured their “Teutonic Eccentricities” throughout the nation.

In 1889, they made a leap that truly cements their place in vaudeville history: they themselves began to produce their own touring vaudeville shows (see above). Entire variety bills were built around themselves as headliners; such companies crisscrossed the country until the team broke up in 1904.

From 1892-95, they worked up many of what would become their most enduring comedy routines, “The Pool Room” (1892-93), “The Horse Race” (1893-94), and “The Schutzenfest (1894-95). In these classic routines, Fields would typically present himself as an expert at some faddish American recreation and attempt to teach it to Weber. Along the way, he would mangle the game’s already-confusing terminology, compounding Weber’s confusion, which in turn compounded Fields’ frustration. The situation would escalate like a cyclone until the two were hitting each other in the stomach, braining each other with canes, and otherwise expressing themselves through violence. Part of the charm was that – as in Laurel and Hardy – Fields “the expert” really knew no more than Weber did to begin with.

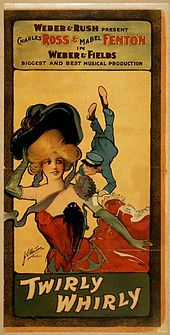

In 1893, the boys made their Broadway debut at the Park Theatre thus helping to further legitimize a performance style that had evolved in the smokey dives of the Bowery. In 1896, they made a huge hit at Hammerstein’s Victoria with a medley of their best routines, and a parody of one of the other acts on the bill, the quick change artist Fregoli. These successes, and the money made from their touring vaudeville shows, permitted them to open their own Broadway theatre, Weber and Fields Music Hall, in 1896. This rather astounding development provides another stark contrast with our own times: imagine Nathan Lane buying his own Broadway theatre, then stuffing each season with specially-commissioned vehicles for himself. Though Weber and Fields continued to present vaudeville bills at the Music Hall (and their touring companies), the real attraction were book shows written as parodies of contemporary Broadway hits. Thus it was the “Forbidden Broadway” of its day, only with full casts, elaborate expensive scenery and full length books and scores. Typical titles: The Geezer, Quo Vass Iss?, Barbara Fidgety,and Fiddle-dee-dee.

For eight years, Weber and Fields Music Hall was a beloved Broadway institution. In 1904, creative and business differences drove the men apart. They officially split, although on numerous occasions throughout the years they briefly teamed up as producers and performers on numerous occasions. Both continued to produce on their own. Weber kept the Music Hall, but Fields was the more successful producer, becoming by 1911 “The King of Broadway”. They made some of the first comedy albums together, mostly in the mid-teens (1912-1915. Listen to them here).

Around the same time, they began to make silent comedy shorts, most notably for Mack Sennett. Here they are in a great publicity still with Mabel Normand:

For such big stars their screen career was surprisingly spotty. They sporadically gave it a shot several times during their last three decades, but they were already older men by that point, set in their ways, and it was ultimately not their medium. They also had their own radio show in the late 1920s, which obviously didn’t allow for slapstick, but was tailor made for their malapropisms. When the Palace held its historic last two-a-day in May 1932, Weber and Fields, whose long career stretched back to the 1870s, was on the bill. Their last live performance was on the very first bill at Radio City Music Hall, later that year.

Like Citizen Kane’s Mr. Bernstein, Weber and Fields were there before the beginning and after the end. As late as 1939, Lew Fields portrayed himself in the Astaire and Rogers film The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle.

A team offstage as well as on, they died (as they were born) within a few months of each other, Fields in 1941, Weber in 1942. Those were good years for a mock-German comedy act to check out of this life, I think.

**Obligatory Disclaimer: It is the official position of this blog that Caucasians-in-Blackface is NEVER okay. It was bad then, and it’s bad now. We occasionally show images depicting the practice, or refer to it in our writing, because it is necessary to tell the story of American show business, which like the history of humanity, is a mix of good and bad.

Exciting news! The new Archeophone CD for which I co-wrote the liner notes: Joe Weber and Lew Fields: The Mike and Meyer Files, is now available to pre-order, and will officially drop on May 31. Don’t go thinking you’ll have done your due diligence by reading this post. The content in the liner notes is far more extensive, quite different, and the collaborative work of myself, Fields’ scholar Marc Fields, and Archeophone’s chief bottle washer Richard Martin. Not to mention the direct experience of the team themselves on the CDs. Place your order now! I said NOW! Go here.

Three books I must recommend for further reading: From the Bowery to Broadway : Lew Fields and the Roots of American Popular Theater (by Lew’s relatives Armond Fields and L. Marc Fields) is really the Bible on Weber and Fields and much else. To find out more about vaudeville past and present, including the seminal team of Weber and Fields, consult No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous, and my related book Chain of Fools: Silent Comedy and Its Legacies from Nickelodeons to Youtube

[…] Read about their act here. https://www.musicals101.com/weberfields.htm 29th & Broadway NYC https://travsd.wordpress.com/2010/01/01/stars-of-vaudeville-100-weber-and-fields/ Anna Held was the big star in Higgledy […]

LikeLike

[…] Full article may be found here: https://travsd.wordpress.com/2010/01/01/stars-of-vaudeville-100-weber-and-fields/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Dick is going to take Ma to see Weber and Fields. I suppose she will be able to nearly taste “Lena and Fritz.” (follow this link for an interesting article about the Weber and Fields comedy duo: https://travsd.wordpress.com/2010/01/01/stars-of-vaudeville-100-weber-and-fields/) […]

LikeLike

who was the old comedy duo that had a punch line “dis must be the place?”

LikeLike

Hello, Nice site. I own an previously unknown 20,000 page archive containing all of Edgar Smith’s work, and the collaborations of many others. This work is original, containing hundreds of manuscripts and typescripts of Weber and Fields material. For instance, I have the original mosquito trust piece, just as it rolled off of the typewriter, with hand changes. I also have the original script where a pie in the faced was used for the first time. Comedy DNA. If you have an interest in reviewing or receiving any of this historical comedy, contact me at atomicrev@sbcglobal.net or 847-409-1156. Best Regards, Kevin.

LikeLike

[…] He introduced acts like Jerry and Helen Cohan (parents of George M. Cohan) and comedians Weber & Fields (you can see their act here). Mrs. Tom Thumb performed, and animal trainer Fred Kyle brought his […]

LikeLike

If you are interested in film of the real Webber and Fileds, I have it. It’s their famous Pool Hall Routine, which was among several Vaudeville acts filmed by Dr. Lee deForest in the early to mid 1920s.

LikeLike

Weber and Fields also play themselves in a scene in the (awful) Hollywood biopic of Lillian Russell. This is worth watching ONLY for the Weber and Fields scene (and Eddie Foy,Jr.)

LikeLike

Weber and Fields were filmed by the De Forest Co. in 1923 (in an early sound film) performing their POOL ROOM SKETCH. The De Forest films were reissued on DVD a number of years ago – but this collection seems to be out of print.

LikeLike

FIRST SOUND OF MOVIES is still available. I am its Producer. It is on Amazon and our website: inkwellimagesink.com.

LikeLike

There is an earlier biography by Felix Isman called WEBER AND FIELDS and published in the 1920s.

LikeLike

[…] He came to New York in 1890, becoming popular on the stage of the Casino theatre as well as Weber & Fields music hall. He was prized for his comical characterizations as kindly old men, and played several […]

LikeLike

[…] Bial’s (where she was held over for 20 weeks) and toured with vaudeville companies managed by Weber & Fields and Hyde & Behman. In 1899 she met and married George M. Cohan. The timing was fortuitous; he […]

LikeLike

[…] born infant), a stuffed mermaid, a tattooed man, a chicken with a human face, and comedians Weber & Fields, whom he’d met whilst working at Bunnell’s […]

LikeLike

[…] at age 9, and thereafter alternated vaudeville and Broadway bookings, including several shows of Weber & Fields (and, after their split, Fields himself). He later broke into films, acting with many of the great […]

LikeLike

[…] Strapped for acts, Advanced Vaudeville hung on for a few years by switching to unit shows (as Weber and Fields and others had done in the 1880s and 90s), a move that was feasible since they owned all of the […]

LikeLike

[…] for tab shows based on popular comic strips like Mutt and Jeff, the Yellow Kid, and Happy Hooligan. Weber and Fields, Montgomery and Stone, Eddie Cantor and Billy Reeves are all artists who can be said to have been […]

LikeLike

[…] performance at New York’s Casino Theatre Roof Garden set the town abuzz, with her impressions of Weber and Fields, Faye Templeton and Lillian Russell. Later that year she played London and Paris. Her repertoire […]

LikeLike

[…] show My Little Margie. Before that though, he was one half of the team Kolb and Dill, among the top Weber and Fields copy-cat acts of their day. Kolb and his partner Max Dill grew up together in Cleveland, where they […]

LikeLike

[…] punching, hitting and committing all manner of mayhem on each other. They were the forerunners of Weber and Fields, the Three Stooges, and countless […]

LikeLike

[…] to be better known as Cary Grant). The trio toured for six months before breaking up. He was in two Lew Fields musicals Ritz Girls of 19 and 22 and Snapshots of 1923. He teamed up for awhile with a man named […]

LikeLike

[…] Your Arms Around Me, Honey”. Throughout the teens she alternated vaudeville with musicals such as Lew Fields’ The Henpecks (1911, also with the Castles) and the Shuberts’ The Whirl of Society (1912, also with […]

LikeLike

[…] on this day in 1863, Sam Bernard is cut of the same cloth as his friends Weber & Fields. He hailed from the same Lower East Side neighborhood, debuted the same year (1876, at the […]

LikeLike

[…] Ebsen was hired his first day in New York, to be in the Lew Fields show Present Arms. The fairy tale beginning quickly evaporated though when he was fired at the end […]

LikeLike

[…] they had a bicycle accident. Their ensuing argument was thought by bystanders to be “as funny as Weber and Fields” and so they began to cultivate an act. They started out in Bowery saloons doing song and dance […]

LikeLike

[…] those days most comedians self-consciously crafted personae for themselves over a number of years. Weber and Fields didn’t speak in Dutch malapropisms and hit each other over the head at home. Rogers (like most […]

LikeLike

[…] the Sophomore.” This act, which satirized college students, aimed to be more intelligent than the Weber and Fields-style knockabout Wynn was accustomed to seeing on stage. (“Rah! rah! rah! who pays the bills? Ma […]

LikeLike

[…] a star in musicals, operas and operettas. In 1899, she replaced Fay Templeton as the female lead of Weber and Fields‘ burlesque company, starring in shows with unbelievable names like, Whirligig, […]

LikeLike

[…] contemporary melodrama for nearly three decades when she gained her greatest fame as a member of Weber and Fields’ stock company, and later as the star of George M. Cohan’s 45 Minutes to Broadway. (If modern […]

LikeLike

[…] or “slapstick” , it has a rich tradition stretching back through the centuries. Weber and Fields were doing it before the stooges were even born, so , moms, DON’T BLAME THE […]

LikeLike

[…] and he quickly established himself as an eccentric comedian, and around 1904 started working for Lew Fields as a utility man, playing character roles with names like “Souseberry Lushmore.” He had a […]

LikeLike

[…] Zeppo). They were as good therefore as four acts in one, combining the appeal of Charlie Chaplin, Weber & Fields, Milton Berle and, well, Zeppo, all in one act. W.C. Fields called them “the one act I could […]

LikeLike

[…] performance at New York’s Casino Theatre Roof Garden set the town abuzz, with her impressions of Weber and Fields, Faye Templeton and Lillian Russell. later that year she played London and Paris. Her repertoire […]

LikeLike

[…] girl. In the latter capacity she soon found herself working shows for the likes of Hammerstein and Weber and Fields. She first tried her antics in a Weber and Fields show in an exaggerated attempt to get over. Though […]

LikeLike

Ah, there is one “From the Bowery to Broadway”—one of the coolest books I’ve ever read and far more illuminating about vaudeville than most actual books that purport to be about vaudeville. It’s by a couple of Fields’ descendants, Marc and Armoind Fields, I believe.

LikeLike

Worth a book of their own!!! Thanks again for these capsule bios…I really enjoy them…

LikeLike