(adapted from a talk given at the Barnum Museum, Bridgeport, CT, November 2005)

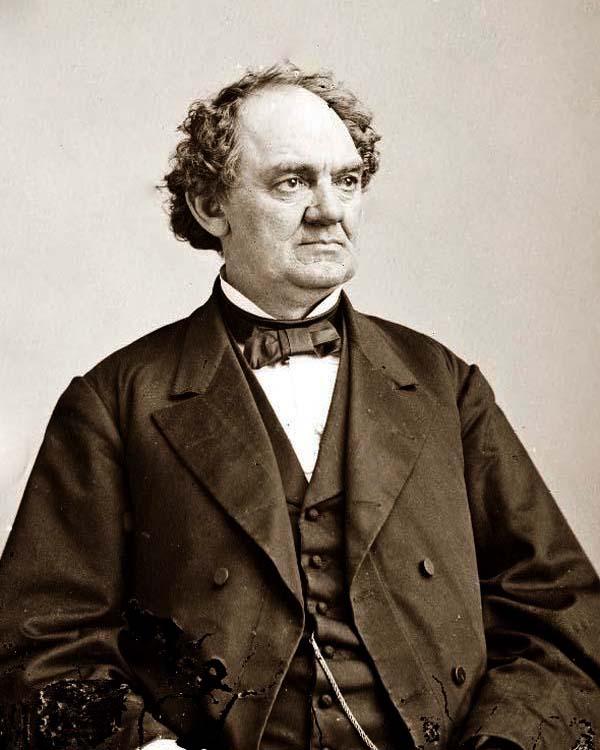

Most books on vaudeville devote at most a mention or two to P.T. Barnum (July 5, 1810 – April 5, 1891). In No Applause, I spent half a chapter on the man, and at a pivotal point in the history. He deserves it.

If George Washington is the Father of our Country, P.T. Barnum is the Father of the Soul of Modern America, of Public Relations, of Show Business. He is one of the premier (and most convincing) apologists for the capitalist system. His autobiography Struggles and Triumphs sold second only to the Bible in the 19th century not only because Barnum lived one of the most amazing lives ever recorded, but because the book is a testament through and through to the American way of life.

It’s easy to mythologize someone like that (since I just did) so it’s useful to remember that a myth is often a projection or a distillation of certain qualities or inclinations prized by the society at large. So while most of this essay will be about how we became a Barnum Nation, it’s worthwhile to second look at how we were already a Barnum nation and how that fact gave us Barnum.

Other than the massive circus organization that continues to bear his name, Barnum is probably best remembered today for a quote he apparently never said (but ought to have): “There’s a sucker born every minute”. That’s quite a thing to say, whether he said it or not. More interesting to me is the fact that when it is quoted, it is generally done NOT with disgust and indignation, but with something like an admiring smile. How can this be? It is the sentiment of a rogue! It is the maxim of a con artist! I suspect the reason why the quote doesn’t make us hot under the collar is that, even though it’s wrong to swindle somebody, that doesn’t stop the process from sometimes being a damn good joke. If I steal all my friend’s clothes while he’s taking a shower in the locker room, to him it’s a mean trick but to everyone else it’s entertainment. Chances are, he’ll laugh about it himself once he gets his clothes back.

They don’t teach this in most grammar schools, but America actually has two mythical foundings. There’s the one at Plymouth Rock, the attempt to build a Puritan utopia in New England. And there’s the other one, in which the Dutch were said to swindle the Indians out of Manhattan for a handful of beads. To oversimplify, the Puritan Way was “work, pray, do good works, and in the end your reward is heaven.” The more earthly and earthy philosophy is: “You mean I have to wait until I die to have any pleasure and even then there’s no guarantee? What’s wrong with enjoying life now?” A crucial figure, if not THE crucial figure in transforming American society from one of the first type to one of the second, was P.T. Barnum.

Barnum grew up in Bethel, Connecticut. Even in the 19th century, the state was still overwhelmingly Puritan (or Congregationalist, as the creed came to be known.) Barnum was raised in the Universalist faith. As the name implies, Universalists believed everyone was going to heaven. This was a relatively new heresy at the time, one which I believe provided Barnum with the intellectual ammunition he needed when he helped bring about the Amusement Revolution.

Consult Roget’s Thesaurus under “amusement”: you will discover an amazingly broad list of human activities, embracing holidays, sports, games, jokes, toys, parties, dancing, theatre, carnivals etc etc etc. Throughout Medieval times most of these activities answered the description of folk practices. Professionalism in fun was discouraged, even outlawed. Performers and exhibitors were transients; they moved from town to town so they wouldn’t get arrested. In earliest days they would perform or exhibit outdoors. Later, theatres were built for the more legitimate, established companies, but the transient performer and exhibitor exist all the way to modern times.

FOR CLARITY:

PERFORMER: actor, clown, magician, musician, puppeteer, acrobat, juggler, fire eater, dancer etc etc etc.

EXHIBITOR: A person who exhibits trained or rare beasts, novel machines (automata, magic lanterns, etc), panorama displays, and deformed humans or other curiosities of nature.

All of this predates Barnum by centuries. Which is why we say we were already a Barnum nation before Barnum was born. In fact, as has been pointed out, Barnum originated virtually none of his famous attractions. He sought them out, discovered them when they were already being exhibited by someone else, bought their manager’s out and then gave them the benefit of his own genius for exploitation, making unprecedented use of the newly inexpensive newspapers which had only been on the scene since the 1830s.

The first stage of his revolution was the legitimizing of spectacle. When Barnum started out, there were already a few museums in existence: Peal’s in Philadelphia, Kimball’s in Boston, Scudders in New York. More generally exhibitors would rent a storefront or hall, or put up a tent, or open the back of their wagon in order to display a curiosity, which was promoted with newspaper ads and handbills. Barnum started this way himself with his first attraction, Joice Heth the purported nurse of George Washington. He had been a clerk, bookseller, newspaper publisher and promoter of lotteries before purchasing the services of slave woman Heth in 1835. He made a brief stir showing her off, but she died within months, and Barnum traveled with circuses for the next five years before buying Scudder’s Museum.

Scudder’s was a shabby, run-down establishment full of taxidermy displays before Barnum transformed it into the American Museum. He legitimized it by making it fabulous. The building was an advertisement for itself. He placed the flags of all the nations of the world on the roof; they could be seen a mile away. There were 100 oval shaped paintings of animals on the outside of the building. Inside, the building was the equal of every other existing show or exhibition put together: fortune tellers, jugglers, snake charmers, fat boys, flea circuses, a dog who could knit, an orangutan, phrenologists, the Feejee Mermaid, the Wooly Horse, the midget Tom Thumb, a beluga whale etc etc etc. THEN Barnum bought what was then an unprecedented amount of advertising. Billboards, ads on wagons, ads in newspapers. On top of this there was the actual coverage he secured in news items about his exhibitions (and his frauds).

At the same time he professionalized and created the amusement industry, Barnum legitimized it by trying to wipe out its bad associations. Such show business as existed back then was in total disrepute, not just because the opinion makers were Puritans and Victorians, but because it deserved to be disreputable. Variety entertainment was usually presented in saloons, and so invariably accompanied by drunkenness, gambling, prostitution, and so forth. This was no less true of theatres, which were famous for racy plays and assignations of ladies of the evening.

Dubious characters were thrown out of Barnum’s American Museum. Yes, he presented freak shows – but freak shows with class. Barnum and Tom Thumb even gave a command performance for Queen Victoria. Furthermore, after he’d been operating a number of years Barnum converted to temperance and began presenting respectable anti-alcohol melodramas in his so-called lecture room. It became socially acceptable to attend Barnum’s theatre. At around the same time (1850) he engineered the highly successful American tour of the Swedish Nightingale Jenny Lind. A popular singer on the continent, in Barnum’s hands she acquired the image of a sweet, soulful, feminine angel, someone a clergyman would be proud to have sing in his parlor. The usual image then of a professional singer was closer to the character played by Marlene Dietrich in Destry Rides Again.

These are the elements of Barnum’s contribution to the foundations of show business: professionalization, propriety, public relations. His career was to last another 40 years, during which he would enjoy countless more triumphs like these, but those initial breakthroughs were the real turning point.

One thing about explorers is that, once they’ve blazed a new trail it’s usually a little while before others follow in their footsteps. Mass settlement of North America didn’t start until decades of visits by the first modern European explorers; and we still haven’t been back to the moon. Likewise, it was a few decades after Barnum’s revolution that others began to follow his example in any kind of applied and significant way.

One of these was a gentleman commonly considered the Father of Vaudeville. Antonio “Tony” Pastor (not to be confused with the big band singer of the same name). Billed as a child prodigy, Pastor sang as a little boy at temperance meetings and (significantly) at Barnum’s museum. He became a circus ringmaster at a young age and did that for many years until the Civil War broke out, which naturally curtailed the activities of most traveling shows. Pastor went back to his hometown New York City and, though he was a teetotaler, started singing in saloons. Pastor’s role always seemed a lot like the “chairman” in the British Music Hall. He sang songs but also functioned as master of ceremonies. In 1865 he opened his first music hall. Technically, the place was a bar, but right away he set about making enhancements that indicated the direction in which he intended to go.

Pastor promised “fun without vulgarity”, throwing any troublemakers out on their ear. In 1881, he moved his premises to an area around Union Square then known as the Rialto. It was the legitimate theatre district, but also the ladies’ shopping district. Furthermore, he removed alcohol from the premises completely, just as Barnum had done before him. This is the first time this had been done in a music hall. The idea was to attract women and children in addition to men. He mounted a massive advertising campaign, offering door prizes: coal, flour, dishes, sacks of potatoes, dress patterns, sewing machines and even whole dresses. The show, too, had to be cleaned up. Instead of rowdy saloon acts, he set new standards for gentility. Pastor’s most famous creation was Lillian Russell, a refined operatic singer whom was held up to be the most beautiful woman in the world. Really Helen Leonard from Iowa, pastor proclaimed he’d imported her from England at great trouble and expense. Women idolized Russell and many of his other famous female singing stars, like May Irwin, Fay Templeton and Blanche Ring. Of course Barnum had set the precedent with Jenny Lind.

For the kids, of course, there was clowning, magic, acrobatics andthat staple of vaudeville, the kiddie act. A songwriter named Gus Edwards (most famous for the song “In the Good Old Summertime”), got his start at Tony Pastor’s and produced a number of acts over the decades starring children, with names like “the Newsboy Quintet” and “the Nine Country Kids”. And kids must have loved the fact that Pastor still dressed like a ringmaster, with top hat, swallowtail coat and handlebar moustache.

So that’s one line leading from Barnum to vaudeville – Tony Pastor and “refined vaudeville”. Here’s another –

In the wake of the success of Barnum’s American museum, numerous others crept up, none of them near the scale of Barnum’s. In fact, most of them were quite shabby. New York had perhaps dozens of them, most of them clustered around the Bowery. They became known as dime museums because of their popular prices. They generally offered low rent versions of the freakier aspects of Barnum’s, the sort of attractions that would later be associated with sideshows: Zip the Pinhead, JoJo the Dog-faced Boy, and similar unfortunate specimens.

One of the pre-eminent New York dime museums was a place called Bunnell’s. A young man who worked both there and at P.T. Barnum’s circus was named Benjamin Franklin (“B.F.”) Keith. (K as in RKO). Keith a Yankee from New Hampshire and in 1883 he moved to Boston to start a museum he called the Gaiety. On view there you could find a stuffed mermaid, a tattooed man, a chicken with a human face and Baby Alice (a prematurely born human infant). Upstairs in a little hall, he presented variety shows. By all accounts the operation wasn’t doing too well until one day he hired an old circus friend named Edward Albee (the grandfather by adoption of the famous playwright). Albee was a down-Mainer from a rich family, and he worked circuses as a grafter, specializing in short-changing the customers. With Albee as his general manager, Keith abandoned the freakish dime museum side of Barnum’s legacy and adopted a little professionalism, propriety and public relations. The Keith organization in all its forms and incarnations is the heart of the vaudeville story and embraces far more than can be touched on in this essay. It became the dominant Big Time chain in the country eventually encompassing 400 theatres including most of the important vaudeville houses in the country. The organization was around for 50 years; here we just want to touch on Barnum’s legacies.

Professionalism. Keith and Albee made a pile of money doing pirated versions of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas which they presented to the public at a tenth of the cost of what the opera houses charged. With these proceeds they built ever more fabulous theatre in Boston, then in Providence, Philadelphia, New York, then all over the country. Just as Barnum had made the American Museum architecturally conspicuous, Albee (the driving force behind Keith) made their vaudeville houses showplaces in and of themselves. (See page 96 of No Applause for a description of one of their theatres).

Propriety. Second, largely at Mrs. Keith’s instigation, Keith’s theatres had to be proper. Anyone guilty of swearing or saying anything otherwise objectionable, even “slob” or “Holy Gee”, would be fired. The performers soon learned to toe the line. Keith’s became known as the Sunday School Circuit. (For a description of one of the premier wholesome acts of the day, see yesterday’s post about the Four Cohans).

Public Relations. But when we think of Barnum today we don’t necessarily think first of propriety—that was really just the most successful of his p.r. campaigns. When it came to p.r. flair few of the vaudeville managers had anything like a Barnumesque inventiveness or charm, Tony Pastor and Willie Hammerstein (p.128 of No Applause) being exceptions. Most were bland, colorless CEOs. Instead, interestingly, the best promoters in vaudeville were the acts themselves. Harry Houdini’s entire career was a series of stunts, ensuring that his names would stay in the newspapers throughout his career. Eva Tanguay billed herself as “The Girl Who Made Vaudeville Famous”. She got headlines by beating up fellow chorus girls and showing up in a costume made of Lincoln pennies.

Hoodwinking the public was good sport and good business. A cockney performer named Muriel Harding became famous as Olga Petrova. She never ceased using her fake Russian accent onstage or off. A singer named Louise Kerlin took the name of novelist Theodore Dreiser’s brother Paul Dresser, a popular songwriter. Dresser wrote songs for Louise to sing and have her out to be his sister: Louise Dresser. A Chinese magician named Chung Ling Soo made life hell for a Chinese magician named Ching Ling Foo. Chung was a fake (his real name was Robinson) but he was actually a much better magician than Ching. Besides, by then, Ching had his hands full with other copycats, such as Tung Pin Soo, Long Tack Sam, Han Ping Chien, Li Ho Chang, Rush Ling Toy and ten or so others. The Great Houdini was not only hounded by the Great Boudini, but – intentionally — the Great Hardeen, who just happened to be Houdini’s brother Dash. Will Rogers would ride into town on his horse with a sign advertising his performances. Al Jolson put an ad in Variety that read “Watch Me – I’m a Wow”. Does the spirit informing all this showmanship sound familiar? It ought to. 100,000 others have carried the Barnum philosophy forward to the present day, for better or worse – probably both. And lest ye have doubt…

For more posts related to P.T. Barnum go here.

To find out more about the history of vaudeville, including a whole chapter on how P.T. Barnum set the stage, consult No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous, available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and wherever nutty books are sold.

[…] learning the fundamentals of museum administration and management, then toured a bit with P.T. Barnum’s circus. He eventually settled in Boston, where he opened the Gaiety Museum in 1883. Here he […]

LikeLike

[…] of marketing that is whimsical, poetical, prankish, and itself theatrical. In most senses, P.T. Barnum can be considered the inventor of this art form, although, like many great inventors, all he really […]

LikeLike

[…] Dan Rice was one of the most important show business figures of the 19th century, up there with P.T. Barnum, Tony Pastor, and Harrigan and Hart. Many people aver that he was the visual model for Uncle Sam. […]

LikeLike

[…] By the time he reached puberty, Pastor had already accumulated an impressive resume, having sung at Barnum’s Museum as a “Child Prodigy”, danced in a blackface act in Raymond and Waring Menagerie, and […]

LikeLike

[…] if P.T. Barnum had lived he would have turned 200 years old on July 5 of this year, which is about the age he once […]

LikeLike

[…] is the birthday of Chang and Eng, the original Siamese Twins. Most famously exhibited by P.T. Barnum, a large portion of their adult lives was spent running their North Carolina plantation (which ran […]

LikeLike

[…] caught the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey three ring show roughly once a decade since the mid-1970s. Surprisingly this year was […]

LikeLike

[…] than 5 hours a night. In addition, Houdini was one of the greatest publicists ever, up there with Barnum, Ziegfeld and Billy Rose.Will Rogers called him “the greatest showman of our time by far”. No […]

LikeLike

Your blog is outstanding!

Here is a post about P.T. Barnum bringing his show to Sandusky in 1878:

http://sanduskyhistory.blogspot.com/search?q=barnum

LikeLike

Thanks, I’ll definitely check it out. And thanks for the kind words about Travalanche. please spread the word!

LikeLike