Antonio “Tony” Pastor was born on this day in New York City in 1832. He first sang publicly at a temperance meeting at the age of 9. By the time he reached puberty, Pastor had already accumulated an impressive resume, having sung at Barnum’s Museum as a “Child Prodigy”, danced in a blackface** act in Raymond and Waring Menagerie, and performed juvenile roles and acrobatic turns with Welch’s National Amphitheatre. A crucial break came when the ringmaster at the circus where he was working dropped dead, creating a vacancy which Pastor was ready to fill, even though he was still a teenager. In those days, the job called for singing, dancing, and acting in the afterpiece, in addition to the familiar announcing chores.

Pastor began performing regularly at a music hall at 444 Broadway, just after the Civil War broke out in 1861. It was such a dive it never had a name; it was always called simply “444”. The bar offered variety entertainment, with Pastor functioning in a role similar to that of the chairman in the English music hall. He doubled as master of ceremonies and a popular singer, presenting his own patriotic songs in support of the war, as well as sentimental and humorous tunes about labor, a subject near and dear to the hearts of his working class clientele. He claimed to have a repertoire of 1500 songs. Favorite Pastor numbers included Down in a Coal Mine, The Great Atlantic Cable, The Monitor and the Merrimac, and The Irish Volunteers. The lyrics to these tunes were published in little songsters and distributed to the audience, who sang along music hall style and walked away with a little souvenir. Reportedly, Pastor had a terrible voice, but audiences loved him anyway, another tribute to his ability as a showman.

In 1865, he took over the Volks Garden at 201 Bowery and renamed it “Tony Pastor’s Opera House.” Though his establishment was no less a bar, he set about making a number of improvements that would set it apart from garden variety concert saloons. Rowdy patrons were expelled from the premises. Advertisements indicated in no uncertain terms the direction in which he was moving, claiming his show was “unalloyed by any indelicate act or expression…fun without vulgarity.”

Part of the impulse to initiate the policy change may have been a genuine conviction on Pastor’s part, he being a man of his times and all. A devout Catholic, he would eventually have a prayer room built in his theatre, and a poor box installed in the lobby. His strongest curse was said to have been “jiminetty”.

But the times themselves must have played a role. A businessman with any instinct seeking to stay afloat in those years of high Victorianism must have been constantly mulling over the tirades of clergymen, temperance advocates, reformist politicians and journalists railing against saloon culture. The so-called Concert Bills of 1862 and 1872 existed and were on the books. As any life-long New Yorker can tell you, such laws are like sleeping grizzly bears. All it takes is the election of a reformist Mayor to jump start the enforcement of such laws and the party is over. A savvy businessman tries to stay two steps ahead of such developments.

If Pastor’s motives weren’t pure as the driven snow, neither was his impulse to court families particularly original. German New Yorkers, suggested a third way between a never-ending debauch…and total abstention from intoxicating liquors. It is impossible to imagine the 4th of July had the Germans never arrived. It is to them we owe hamburgers, cold cuts, hot dogs, mustard, pickles, pretzels, brass bands, and most importantly, beer.

For years, German and Austrian immigrants in New York had enjoyed their own imported type of drinking establishment, known as the beer garden. Beer, as Hogarth taught in his famous engravings, is of a lower order of intoxicant than hard liquor. As depicted by Hogarth, the inhabitants of “Gin Lane”, are a debauched and sordid collection of dregs. In “Beer Street”, life is sane, productive and normal. Similarly, in contrast with the rowdy, whiskey-soaked concert saloons, beer gardens were genteel places, where families went to listen to musical concerts together. Germans had a different relationship with alcohol. Beer and wine were served, but generally consumed responsibly. Relaxation for the Germans did not mean urinating outdoors, crying, fighting, singing dirty songs, and putting lampshades over their heads. One can picture transplanted burgers sedately sipping lager from Rococo steins whilst their apple–cheeked kinder, in shorts and lederhosen, frolicked in Der Garten, supervised by “mama”. Nearby, a string quartet plays music from the old country – a lullaby by Brahms. German families played together, stayed together, didn’t break up the furniture – and surely brought in several times the proceeds.

Furthermore, Pastor’s experience at Barnum’s Museum surely suggested the possibility that variety could and should be presented in a respectable environment. Above all, there hovered the lure of a vastly increased market. The concert saloon clientele consisted of a mere percentage of men. If he could include all the men, plus their wives and children as his potential audience, think of the increased revenue.

By the 1870s, the overall environment was transitioning. “Variety Theatres” and “Music Halls” had arrived and were gradually displacing concert saloons. For the most part, they were a cocktail containing the same ingredients, but mixed to a different formula. Instead of a bar with a theatre attached, it was a theatre with a bar attached. Still disreputable in some quarters, but marginally more genteel. Some were quite fancy, but they were still men’s joints. But here and there, these institutions began to sponsor special cleaned-up ladies matinees, temporarily banishing the beer and cigars for a few hours. Pastor, more than any other saloon man, saw the potential in this trend and put himself at the center of the movement.

In 1875 Pastor moved “up” again, out of the ever-degenerating Bowery to 585 Broadway, near the present-day site of New York University. Liquor was still served, but he was in a respectable neighborhood, in close proximity to the most popular theatre in the city, the Theatre Comique, where the Irish comedy team of Harrigan and Hart starred and were soon to be proprietors. This stretch of Broadway had become one of New York’s first official theatre districts, due to the proliferation of nearby minstrel halls in the 1850s. Pastor’s establishment was also now an easy distance from the city’s main shopping district, known as the Ladies Mile, and the emerging theatrical strip on 14th Street, known as the Rialto.

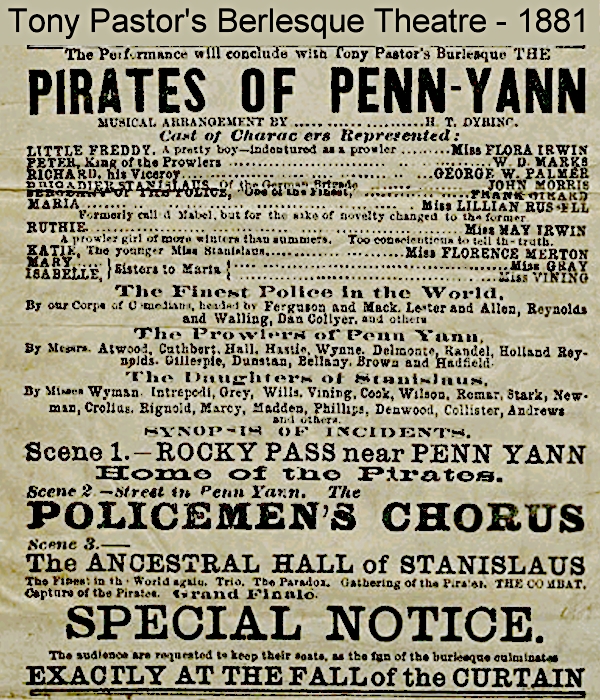

He made the leap to the Rialto itself in 1881, to a theatre literally located in Tammany Hall, right on Union Square. At first, he tried to follow in the footsteps of Harrigan and Hart, who had enjoyed major success by expanding to full length form the comic afterpieces that still capped every variety bill. After the team assumed proprietorship of the Theatre Comique in 1876, a series of their sketches featuring a loveable character named Dan Mulligan became so popular that they became the whole show. Many regard them as forerunners of today’s musical comedies. The plays featured the so-called Mulligan Guards, a rag-tag Irish militia mustered by the title character. From 1878-81 there were numerous sequels including The Mulligan Guards’ Christmas, The Mulligan Guards’ Picnic, The Mulligan Guards’ Surprise, The Mulligan Guards’ Ball, the Mulligan Guards’ Chowder (as a clambake was sometimes called), the Mulligan Guards’ Nominee, and The Mulligan’s Silver Wedding.

You can’t argue with success. To Pastor, the expansion of the variety afterpiece seemed a winning formula. He had been presenting such afterpieces at his various venues since 1865, usually parodies of classics and popular shows of the day, as had been the tradition since minstrel times. In 1881, he inaugurated his move into the Tammany location with The Pie-Rats of Pen-Yan, a parody of Gilbert and Sullivan’s recent hit The Pirates of Penzance. But it didn’t click. Within a few months, Pastor settled down to concentrate on his great contribution to American popular culture: straight, clean variety.

This is the common marker for the official genesis of vaudeville as an organized and respectable institution. Recall that only men went to the variety theatre at this time, and they only went when they were misbehaving. Pastor instituted new policies: no drinking, smoking, no vulgarity on stage, no mashers. The fact that there was a bar next door (in the Tammany building, but technically outside his own premises) helped him ease his customers into this radical new practice. Next, Pastor widely publicized his revolutionary policies. In ads, he referred to his theatre as “the Great Family Resort of the City.” To actively attract the better half, he started by making Friday ladies’ night, offering door prizes: dishes, coal, bonnets, flour, dress patterns, sacks of potatoes. When he changed the prizes to sewing machines and silk dresses the trickle of estrogen into his theatre became a flood.

One feature of that 1881 production of Pie-Rats that Pastor retained was the acme of his efforts as a promoter and a by-product of his outreach to women: the singer Lillian Russell.

Russell represented something new in variety. A more typical female singer in those days was one of Pastor’s other stars, Maggie Cline “The Irish Queen”. Irish Mag’s sentimental repertoire ranged from humorous tunes to tear-jerkers, but her fame rested largely on a single signature song, a rowdy, raucous, crowd-pleasing number called “Throw Him Down, McClosky”, a song about a pugilistic bout. On the refrain, the audience sang along music hall style and everyone backstage would throw whatever they could get their hands on, onto the stage. While there is nothing technically objectionable about Cline or her song, we see right off the bat that it is a saloon act. The fact that it is a crowd-pleaser is in its favor, but in no sense does it represent a break with the past.

The same came not be said of Russell, who in the best vaudeville spirit, Pastor is said to have “created”. In her day, she was the most famous woman in the world, the paragon of the age, the epitome of all that women aspired to be, and that all men aspired to possess – and one of vaudeville’s and the legitimate stage’s biggest stars. To generate this furor, Pastor relied largely on the template Barnum had used in promoting Jenny Lind, billing her as a young woman with the soul and voice of an angel. But Pastor went the old showman one better by starting from scratch with Russell. After all, Lind had already been a sensation in Europe when Barnum “discovered” her. When Pastor came upon Russell, she was merely Helen Louise Leonard, an operatically trained singer from Clinton, Iowa. Bit parts in H.M.S. Pinafore and Evangeline at the Park Theatre in Brooklyn brought her to Pastor’s attention. Captivated by her voice and her beauty, he booked her for his oldBroadway Music Hall in 1880, then sent her out to San Francisco and a tour of Western mining towns to get a bit of seasoning.

When she returned, Pastor gave the girl her stage name (meant to sound like “Lily and Russell”). He began to tout her as the most beautiful woman in the world. When she returned to star in The Pie-Rats of Penn Yan in 1881, he billed her in true Barnum fashion as “the beautiful English ballad singer I’ve imported at great trouble and expense.”

While Russell would appear in vaudeville from time to time over the decades, she grew to be primarily a star of operetta and the just-hatching musical comedy. Many of Pastor’s female singing stars such as Russell, Fay Templeton, Blanche Ring, and Mae Irwin and many others moved gracefully between the two stages, which enhanced the reputation of Pastor’s theatre. Far from the rough-and-tumble precincts of the Bowery, Pastor’s new variety theatre was surrounded by legitimate theatres and starred legitimate stars.

Pastor’s new lady stars were presented as ideals, as soulful and feminine – in touch with that higher realm wherein Beauty and Goodness were synonymous. “Airy, Fairy” Lillian Russell was known as “The American Beauty”. Blanche Ring was called by critics “radiant”. Lottie Gilson was “The Little Magnet”. The singers would be clad in elaborate costumes, often with an accessory prop such as a parasol or a fur muffler. Interestingly, these women were at their height in the 1880s and 90s, when the theatrical district was at Union Square, just a dainty trot away from all the new department stores over on the stretch of Sixth Avenue known as Ladies’ Mile. As producer and author Robert Grau put it at the time, the theatres of Union Square were “distinctly popular with the class known as shoppers.” After getting an eyeful of their ideal on the vaudeville stage, women in the audience could then run over and plunder the dress and hat departments at A.T. Stewart’s. As if the stage were not pedestal enough, for awhile there was a vogue for singers to do their act perched high atop a swing, evoking both the public parks and amusement parks that were still coming into existence at that time.

At Pastor’s there were other subtle hints of a changing dynamic on the variety stage. Some his Irish acts began to explore the possibilities of a toned-down approach to exploring their identity. John W. Kelly, known as “The Rolling Mill Man” would simply park himself on the stage on a chair and weave long, humorous, extemporaneous stories based on audience suggestions – an act that could never have been heard, let alone appreciated, in a concert saloon. Song and dance man Pat Rooney, while still dressed in the ridiculous Leprechaun-like outfit that was standard “Irish” attire of the day, is credited with bringing a more three-dimensional, sympathetic approach to his portrayals. Monologist George Fuller Golden rose to fame telling flowery, affectionate anecdotes about his friend Casey.

One of Pastor’s acolytes became the premier producer of that wholesome vaudeville staple known as the kiddie act. German-born Gus Edwards had been discovered by Pastor at age 14, and was hired to be a balcony singer. (It was a convention of the time to occasionally surprise the audience by having a ringer stand up from a seat in the house and join the onstage singer for a number). Edwards was to gain his first fame as a songwriter, penning such classics as “School Days” and “By the Light of the Silvery Moon”. His first kiddie act, the “Newsboy Quintet” included himself as one of the cast members. As he outgrew that act, he went on to produce countless others featuring children hired from auditions: “The Kid Kabaret”, “9 Country Kids”, “School Boys and School Girls” and “A Juvenile Frolic”. Scores of children went through the Edwards machine, which is why he was able to boast such a distinguished alumni: Groucho Marx, Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, Walter Winchell, Eleanor Powell, Mae Murray, Phil Silvers, Bert Wheeler, Jack Pearl, the Duncan Sisters, Sally Rand – these are just some of them. Edwards imitators (and there were many) included Ned Wayburn (who was later to start the premier “college” of vaudeville) and Minnie Marx, who employed not only her unruly sons, but a company of ten others in some of their vaudeville acts. These are just some of the many acorns to fall from Tony Pastor’s oak.

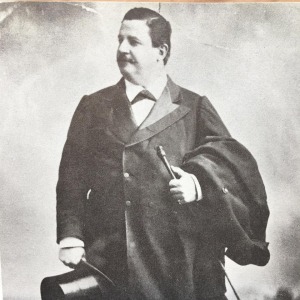

Pastor was a showman of the first water. A genial, hearty presence, he greeted every patron at his theatre personally. He continued to dress like a ringmaster even when he had exchanged the sawdust of the ring for that of the bar-room floor, and then swept the sawdust up completely. With his silk top hat, handlebar mustache, swallowtail coat, and riding boots, he carried a bit of the magic of the big top around with him. He loved children, and began throwing an annual Christmas party with prizes for the kiddies. He was also kind to his performers, never closing an act prior to the end of their contract, and never firing his veteran orchestra members long after old age had stolen their chops.

Interestingly, though he is often known as the “Father of Vaudeville” he refused to use the word vaudeville himself. For him it was always just variety. No frou-frou Gallicisms required.

To learn more about Tony Pastor and the history of vaudeville, consult No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous, available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and wherever nutty books are sold.

**Obligatory Disclaimer: It is the official position of this blog that Caucasians-in-Blackface is NEVER okay. It was bad then, and it’s bad now. We occasionally show images depicting the practice, or refer to it in our writing, because it is necessary to tell the story of American show business, which like the history of humanity, is a mix of good and bad.

[…] Resources:Rachael Reinholtz, House Manager and Special Events Coordinator Harry Phillips, Director of Marketing and Development The State Theatre 404 S. Burdick Street, Kalamazoo, MI 49007 Phone number: (269) 345-6500 https://www.kazoostate.com/about/history/https://travsd.wordpress.com/2010/05/28/stars-of-vaudeville-162-tony-pastor/https://travsd.wordpress…https://hinmancompany.com/portfolio/kalamazoo-state-theatre-kalamazoo-entertainment/https://hinmancompany.com/portfolio/kalamazoo-state-theatre-kalamazoo-entertainment/https://www.grpm.org/organ/https://www.sentinel-standard.com/story/entertainment/music/2020/12/09/michigan-venues-promoters-form-new-trade-group-to-rescue-concert-businesses/115127060/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Before he got to the stage at 444, this son of a Spanish immigrant and his Connecticut-born wife, he had been performing since the age of 14. He had worked as a circus stagehand and animal tender and, in light of his natural charisma, imposing presence and ready command of song and dance, the circus promoted him to the role of ringmaster when its front man suddenly dropped dead. […]

LikeLike

[…] a huge national hit in 1892. The following year she came to the U.S. for very successful runs at Tony Pastor’s, and as Mike Shea’s in Buffalo. She made repeat visits in 1895-96, 1906 and 1907. She […]

LikeLike

Tessie Reardon, one of the characters in “The Yellow Sign” (1895), a classic supernatural tale by Robert W. Chambers, refers to an evening spent at Tony Pastor’s. “We saw Kelly and Baby Barnes the skirt-dancer and – and all the rest,” she says. Do any readers know whether these artistes existed? It would be interesting to know since there is some mystery about precisely when the story is set. It’s a quasi-sequel to “The Repairer of Reputations”, the first tale in Chambers’ wonderfully spooky collection “The King in Yellow”, and this story is supposedly set in 1920; but is it? Interested readers should see the Wikipedia entry on “the Repairer”, where the mystery of the futuristic setting is discussed in some detail.

LikeLike

[…] F.F. Proctor in upstate New York, Beck and Meyerfeld in San Francisco, Kohl and Castle in Chicago, Tony Pastor and Oscar Hammerstein (separately) in Manhattan. Hyde and Behman began in […]

LikeLike

[…] embellished by vaudeville acts. Interestingly, Keith was responding to the operetta fad just as Tony Pastor had, but in the opposite way. Pastor had ennobled his enterprise by embracing operetta’s chic […]

LikeLike

[…] part of a movement to make music hall “respectable”, something similar to the transformation Pastor, Proctor and Keith accomplished in American variety. The married life allowed her to very much the […]

LikeLike

[…] club in 1900. Vaudeville engagements resulted and within a few weeks, he climbed up the ladder from Tony Pastor’s to Keith’s Union Square, and then a tour of the Keith and Proctors wheels. By 1904, he was a […]

LikeLike

[…] Theatre, and she was thereafter a regular there and the other top New York theatres of the day: Tony Pastor’s, Henry Miner’s, and Hyde & Behmans. She was quickly established as the top soubrette of […]

LikeLike

[…] was one of the most important show business figures of the 19th century, up there with P.T. Barnum, Tony Pastor, and Harrigan and Hart. Many people aver that he was the visual model for Uncle Sam. Technically, […]

LikeLike

[…] vaudeville gigs followed, though: Koster & Bial’s, Proctor’s, Hammerstein’s Olympia, Tony Pastor’s Music Hall, the Keith Circuit. They were credited with introducing the cakewalk to mainstream America in their […]

LikeLike

[…] to figure it out. Starting in 1899, this act brought Thurston all over the big time, opening at Tony Pastor’s 14th Street, then the Keith-Orpheum circuit and the Palace in London, where he was held over for […]

LikeLike

[…] became a commonplace stunt for songpluggers). Gradually he began to sell songs to the likes of Tony Pastor and others until success overtook him in the early years of the last […]

LikeLike

[…] Pat Rooney Senior (1844-92) was an old time variety contemporary of Eddie Foy, Harrigan and Hart and Maggie Cline. He sang character songs, did jigs and played the stereotyped Irishman to the hilt – but apparently with a tad more gentility and subtlety than was the wont of most of his compatriots. Pat Rooney, Sr. was one of the major stars of his day, and a staple at Tony Pastor’s. […]

LikeLike

[…] given more attention to in No Applause. He was a pioneer whose career was roughly contemporary with Tony Pastor’s, (post-Civil War era) and claims to have used the term “vaudeville” to describe his […]

LikeLike