(adapted from a talk given at the Ziegfeld Society in April, 2006)

Florenz Ziegfeld was one of the greatest showmen this country every produced. Much ink (and pixels) have been devoted over the years to his most famous creation the Ziegfeld Girl; the current essay will concentrate instead on Ziegfeld’s relationship to vaudeville , both himself as a vaudeville producer, and the many vaudeville stars he booked for his Follies.

Ziegfeld’s father was the director of the sniffy and austere Chicago Musical College. Pere wanted fils to follow in his footsteps in the musical world but the younger Ziegfeld was led astray at a young age by another of America’s greatest showmen when Buffalo Bill’s Wild West came to town. Ziegfeld’s earliest attempts at theatrical entrepreneurship have that sideshow flavor to them. In his early twenties he presented the “Dancing Ducks of Denmark”, which creatures were made to dance by the old sideshow trick of placing the unfortunate fowl on a piece of metal he would heat from below. Canceled by the ASPCA. He also attempted to cash in on “The Invisible Brazilian Fish”, which was just a bowl of water. No trouble with the ASPCA there; there is no record of any qualms the Water Authority may have had.

In 1893, Chicago hosted the World Columbian Exposition, the greatest world’s fair ever presented up until that time. This seminal cultural benchmark had been meant to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to the new world, but it launched a year late. The elder Ziegfeld was named musical director of the event and given a venue on the fairground where he could present music, which he called the Trocadero. Ziegfeld, Jr. was dispatched to Europe to secure classical musicians to perform there. He was an extremely precocious young man. Instead of booking the requested musicians, he booked music hall acts, like trapeze artists, jugglers, and a mentalist. He also booked the expected musical acts, but of a more lowbrow sort than his father could stomach, such as a marching band (marches were the pop music of the day). You can see already that Ziegfeld clearly wanted to be a vaudeville producer and merely snatched at this rare opportunity to do so, even if he was defrauding his own father. The father had no choice but to present these acts, and thus Flo Ziegfeld, Jr. realized his dream of becoming a vaudeville impresario.

The jewel in the crown of the Trocadero Vaudevilles was yet to come, however. Thus far the bill was somewhat mediocre—it needed a star. At the Casino Theater in New York Ziegfeld found one: Sandow the Strong Man. Sandow could lift a man up in each hand, while two men stood on his back. It was said he could hoist 750 lbs of dead weight with one finger and bear the weight of 3200 lbs upon his body. At least that’s what Ziegfeld said.

Ziegfeld’s acumen as a producer resulted in Sandow becoming one of the hits of the fair. He did this by making a sex symbol out of Sandow, allowing him to wear as revealing a costume as was permissible and letting women come back stage and feel his muscles for a fee that was donated to charity. With Sandow as its star, the Trocadero Vaudevilles toured the country throughout the 90s, with a bill that also featured comedian Billy Van, aerialists the Five Jordans, impressionist The Great Amann and six other acts.

After awhile this ran out of steam and Ziegfeld broke into Broadway musicals, famously making a star of French chorine Anna Held, through a barrage of clever stunts such as giving out to the press that she took daily baths in milk to produce beautiful skin. Held’s career was at the center of Ziegfeld’s producing career for about the next decade.

Then, in 1907, Ziegfeld inaugurated the Follies. He’d copped the format from the stage show of the French Folies Bergère, which since 1869 had incorporated elaborate tableaux of beautiful young women as framing devices around music hall talent. Ziegfeld’s shows combined elements of vaudeville and burlesque – and wrapped it in Broadway packaging. In many ways these revues were better than vaudeville. No animal acts or acrobats to sit through…just the top singers and comedy stars, framed by beautiful women wearing opulent costumes. Vaudeville and the Follies were to cross-fertilize each other for the next twenty-five years. And the stars of the Follies, apart from the girls themselves, were invariably the top stars of vaudeville.

This was true of the very first Follies in 1907. The most notable performer on the bill that year was Nora Bayes, who at that time was still using the unfortunate tag “the Wurzburger Girl”. This is because she’d struck it big five years earlier with the song “Down where the Wurzburger flows”. Where exactly that might be, I have no idea. An operatically trained singer, she was known for following in the footsteps of French chanteuse Yvette Guilbert by investing her songs with high dramatic values, emotionally dramatizing her songs so they would touch the heart of the audience. To give you a sense of what that quality was like, Judy Garland was later called the next Nora Bayes. Bayes’ popularity resulted in her becoming the highest paid entertainer in vaudeville at one time, which in turn resulted in her becoming its greatest diva. The tag she later used was more descriptive of her personality: “The Greatest Single Woman Singing Comedian in the World”. It leaves no room for dissent. The second year she partnered with her beau Jack Norworth. The two appeared in the Follies singing “Shine On, Harvest Moon”, which they had supposedly co-written, although something tells me that since Norworth was the man at the piano, and had co-written many other hit songs including “Take Me Out the Ball Game”, the bulk of the labor was his. Like many a vaudeville star, she had a way of hogging the limelight and getting away with whatever she could. I think we can see that Norworth was no slouch — having written “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” (a PRETTY popular song), but he had to settle for the billing: “Nora Bayes, Assisted and Admired by Jack Norworth”. Bayes made Norworth walk her dogs. She made him go outside to smoke, which is another way in which she was ahead of her time.

It’s in the third year of the Follies that Bayes’ attitude and temper tantrums came to a head. The problem was that a talented newcomer threatened to steal the show.

Those who know of husky voiced Sophie Tucker, the Last of the Red Hot Mamas, chiefly from her later days may find it hard to imagine she was ever young. In 1909 she was an earnest young kid with a couple of years of burlesque, vaudeville and restaurant singing under her belt. Hers was a very different sort of talent from Bayes. Bayes was all training, singing, elocution and acting lessons. Tucker was all personality, somebody who shouted her songs, but she was so magnetic that everyone went crazy over her. In terms of ambition, however, she was cut of the same cloth as Bayes. Bayes had come from an Orthodox Jewish family and run away from home the instant she turned 18 so she could go into show business. Tucker had also run away from home, but with an added twist of desperation – she’d also run out on her infant son, whom she left in the care of her parents, so she could concentrate on show biz. In those conservative times, determination to succeed sometimes meant abandoning people you loved. It took a certain kind of person to make that choice, which I think still seems diabolical to our sensibilities.

At any rate, in 1909 Tucker was discovered and booked by Ziegfeld’s backer Marcus Klaw. She writes in her autobiography that she sat around unused for almost the entire rehearsal process. Then, with less than a week to go before opening, Ziegfeld decided the show needed a jungle number to capitalize on Teddy Roosevelt’s recent return from an African safari. A number was hastily written for Tucker. She was going to get to do that ditty and three songs from her repertoire in the show. She’d gotten very little rehearsal time, and amazingly somehow Ziegfeld never saw the numbers prior to opening. It opened for try-outs in Atlantic City, and the audience apparently included just about everybody who was important in show business. This was Sophie Tucker’s big shot. And, apparently, as always happened when Tucker was performing, she brought the house down, not only with the jungle number, but with her set of songs, which she ended up having to double for encores, and then she had several curtain calls. She was a sensation, which sort of took Ziegfeld and the other producers by surprise. They didn’t quite know what they had. Unfortunately, it also took Nora Bayes by surprise. She had been completely upstaged by this development and demanded that Sophie’s numbers be cut from the show. Nora Bayes was the headlining star. The public did not yet know the name Sophie Tucker, as good as she was, so she was cut out of the show. The story has a happy ending though. All of those important people had seen her performance on opening night. The next 55 years or so were pretty much smooth sailing for Sophie Tucker, though she didn’t come back to the Follies. Ironically, Nora Bayes was to quit the 1909 Follies herself. One theory was that it was because of all the attention Ziegfeld paid to Lillian Lorraine, and even that he had called her the prettiest girl in the show, which I guess he was entitled to do, since she was his mistress. But Bayes didn’t see it that way. She left the Follies, never to return, and enjoyed a career full of another two decades of temper tantrums.

The following year, 1910, saw the introduction of two performers who would become perennial favorites of the Follies, and the kernel of what would in time become sort of a loose comedy stock company.

Like Sophie Tucker, Fanny Brice had been discovered working the burlesque wheels. Fans of Funny Girl know this story by heart. She was so ecstatic about the booking that she actually ran around Times Square shouting and flashing her contract to strangers. Some details of Funny Girl were obviously altered. She did get into a contretemps about how to sing the lyrics to “Lovey Joe” but not with Ziegfeld. It was with backer Marcus Klaw. At any rate, Brice was a smash, and the 1910 Follies made her career. Variety called her “The individual hit of the show” and she ended up being perhaps the single performer more identified with the Follies than any other. Unlike most other performers, she THEN translated this success into lucrative vaudeville bookings. Most others became vaudeville stars first, then did the Follies. Brice became a star in the Follies, then also became a headliner in vaudeville.

The other major performer making his Follies debut in 1910 was the Jackie Robinson of show business, the great Bert Williams. By this time Williams was a twenty year veteran of show business, and he’d already made his mark in history several times over. Williams had started out in the waning days of minstrelsy and saloon entertainment in San Francisco’s notorious Barbary Coast. Teaming up with George Walker, the two rose to prominence in the late 1890s as “Two Real Coons”, becoming stars of vaudeville, Broadway, and the infant recording industry. A moment’s reflection will help you realize that this would make them the first black vaudeville stars, the first black Broadway stars, and the first black recording stars. After a remarkable career, however, tragedy struck when George Walker contracted syphilis which caused him to go insane and eventually took his life. Bert Williams now had to develop a solo act. As half of Williams and Walker, he’d always had a character. Walker had played the high-stepping, fast-talking dude, whose get-rich-quick schemes set up the plots that always got the pair into trouble. Williams’ character was the opposite, a slow-witted sad sack for whom nothing went right. This contrasted with his own identity, as an educated, highly intelligent, upper middle class West Indian. To portray this character, so unlike himself, Williams resorted to a common technique of the day, an odd one for a black man: black face. Believe it or not, many, probably most black performers wore blackface in the early days—that’s how they broke into show business in those racist times. In Williams’ case, there was an added element. His real identity was so far from the stereotype it wouldn’t speak to the audiences of those times. He needed to cater to prejudice in order to have a career at all.

Indeed, prejudice in that day was so great, that despite all those accomplishments I just mentioned, the vaudeville, Broadway, and recording credits, when Williams was booked for the Follies, the entire cast threatened to go on strike rather than appear with him. The story goes that Ziegfeld responded by saying “Go if you want to. I can replace every one of you except the one you want me to fire.” I don’t think it’s hyperbole to call this an important moment in American history. Ziegfeld’s adamancy to integrate Williams into the show created a precedent that paved the way for much more progress down the line. Like Brice, Williams was to be very much a staple of the Follies for a good many years.

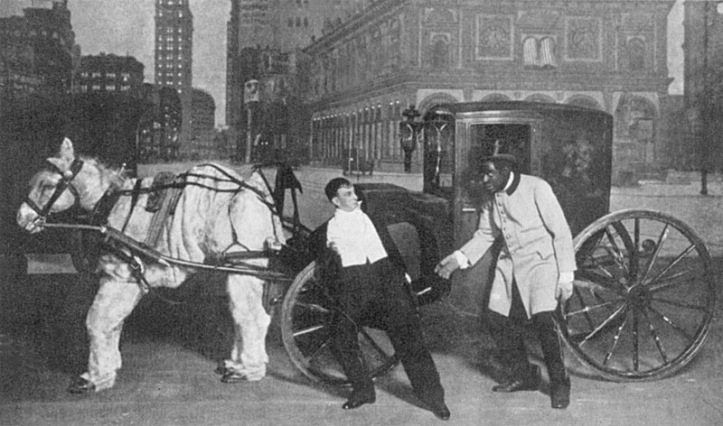

As was another performer whose debut in the Follies occurred the following year, the Australian comedian Leon Errol. Errol was more than just a performer. By the time he appeared in the Follies he’d been writing, directing and producing his own comedies in burlesque for many years, in addition to vaudeville appearances. Errol’s specialty was a comic drunk bit…not a hobo, but a sort of middle-class Rotarian drunk, sneaking home after a night on the town. His signature was a special rubbery legged walk that he did that made it look like that at any second he would go tumbling toward the ground.

In the Follies, he formed a sort of loose comedy team with Bert Williams. In one sketch, Errol played a drunk trying to navigate his way through Grand Central Station, and Williams played a Red Cap who eventually leads him up onto some construction scaffolding on the roof. In another, Errol was the drunk and Williams a hansom cab driver charged with getting him home. Because of his experience as a director, Errol helped stage sections of the Follies shows, until he left in 1915 to follow other pursuits.

1912 was notable for someone who did NOT do the Follies. That year a very different Mae West from the one we know famously turned Ziegfeld down. In those days, she was a singing single, in the same category as Nora Bayes, Fanny Brice and Sophie Tucker. Her niche, as it was in later years, was sex. She sang sexier songs in a sexier way than other singers. This caused her to flop repeatedly in vaudeville, which was very conservative, but in 1911 she’d had some success at Jesse Lasky’s short-lived venture the Folies Bergere (obviously inspired by the success of Ziegfeld’s Follies), and in the Shubert show Vera Violetta with Al Jolson. It was at this point Ziegfeld came knocking, whereupon Mae turned him down cold, claiming that she needed to work in a much more intimate house in order to be properly appreciated. Ahem.

In 1914, Ziegfeld booked Ed Wynn, the “Perfect Fool” for the Follies. Today Wynn is perhaps best known as the floating uncle who sings “I Love to Laugh” in Mary Poppins. In his day he was one of the stage’s most beloved comedians, a very strange talking clown with an egg shaped body, a derby and glasses. The year before, he had played his last engagement in vaudeville on the very first opening bill at the brand new Palace Theater. The Follies gig was to mark a new phase in his career.

The next year, he was joined onstage by another veteran performer: W.C. Fields. Fields would become a staple of the Follies for the next decade or so and it would mark a transition for him also. In 1915 he was still primarily known as a comical juggler. While he had done some onstage talking at various times, most of his 17 years in show business had been as a silent tramp character. It was during his years with the Follies that he transformed into the mumbling, cantankerous character that we know so well from his screen roles. In fact, nearly every W.C. Fields movie features one or more comical bits that he first presented at the Follies. For his first Follies show, Fields presented a spectacular act that he had performed with much success in vaudeville, and which his fans know well from many of his movies. The routine essentially consisted of Fields fooling around for several minutes with a trick pool table. One of the most notorious bits of Follies lore occurred one night while Fields was performing this routine. It seems that while he was performing his act, Ed Wynn had crept onstage and hidden under the pool table without Fields’s knowledge. While Fields was doing his routine, he began to notice all this audience laughter happening in all the wrong places. He realized that Wynn was down there beneath the pool table mugging and making goofy faces at his expense. Without breaking his stride, Fields cracked Wynn on the skull with his pool cue, knocking him out cold. The audience thought it was part of the act and went on laughing harder than ever, and Fields went on with routine.

Probably not because of this incident, Wynn didn’t re-up in the Follies the next year, but instead went on to an amazing string of his own revues specially crafted to showcase him. The Follies had clearly been Wynn’s stepping stone from vaudeville to much greater Broadway success.

Something else important happened in 1915. That was the year Ziegfeld debuted a second regular revue show, the Midnight Frolic. This was a more sophisticated after-hours café type affair where patrons sat at tables and enjoyed booze while watching the show – the epitome of the jazz age. One of his intentions for the Frolic was to use it as a sort of minor league for his potential Follies talent. If their act worked in the Frolic, he’d move them up to the big show.

The most significant performer to debut at the Frolic was perhaps the least likely person to become a Ziegfeld star, and yet he became one of the biggest. Will Rogers had started out performing in circuses and rodeos, until in 1905 he had the brainstorm to bring his act to the vaudeville stage. This sort of thing had never been done before. He brought his horse on stage with him, and did all sorts of rope tricks, and the audience ate it up. Early on, he found that in this new intimate sort of environment, any little remark he might utter would be audible, and to his surprise, audiences laughed at what he said. Initially he hadn’t intended any humor, but in the artificial world of vaudeville, audiences assumed his Oklahoma way of talking was a highly crafted put-on. So he started talking more and more and getting more and more laughs. By the time he started with the Frolic, he’d abandoned his horse but was still doing rope and other tricks in addition to his patter. Initially he bombed at the Frolic and it looked like he was going to be fired. Desperate measures were called for, and Rogers’ wife was the one who supplied the answer. She suggested that he look to the daily newspapers for topical material and base that night’s jokes on that. Believe it or not, this is something else that had never been done. After a half century of the Tonight Show and everything that came after, that’s hard to imagine, but humor based on today’s headlines is actually a relatively new concept historically. Ziegfeld did want to fire Rogers, but the people were laughing so hard at his home-spun remarks in the Frolic that he had to do the opposite – he had to move him up the Follies. Anyone who saw the Will Rogers Follies will have a very vivid picture of what the experience of seeing this cowboy onstage with an army of showgirls must have been like.

The next year, yet another huge star debuted at the Frolic. He was the opposite of Rogers — a scrawny Jewish kid from the Lower East Side named Eddie Cantor. Like Ed Wynn, Cantor is sadly forgotten today, despite having been at the very top of show business during the jazz age, second only to Al Jolson in popularity. In addition to being a crazy comedian, he was also a singer and many of the top tunes of the jazz age like “Yes We Have No Bananas” and “If You Knew Susie” were associated with Cantor. Unlike Rogers, the brash, risk-taking Cantor knew immediately how to make a hit at the Frolic. The audience was full of important people, politicians, millionaires, and so forth. No respecter of persons, Cantor ribbed them mercilessly, famously forcing one VIP to hold a playing card over his head for twenty minutes for a magic trick that never materialized. So, of course, then Cantor moved up to the Follies.

The 1917 Follies featured a bill of comedians that can only be compared to Mount Rushmore. Well, if Mount Rushmore was funny and had comedians instead of presidents. Eddie Cantor, Bert Williams, WC Fields, Will Rogers, and Fanny Brice all performing in the same show. To an old time comedy fan, it’s kind of mind-boggling to imagine. Any Broadway show would be fortunate to have one top comic genius. This one had five. Unlike those battling songstresses Sophie Tucker, Nora Bayes, and Lillian Lorraine (and many others) except for that one incident between Fields and Wynn the comedians were all generous to one another, indulging in a sort of mutual admiration society. The next few Follies will include those five in various combinations and they came to form a sort of informal stock company.

That first year, Cantor stepped in where Leon Errol had stepped out, by forming a sort of loose team with Bert Williams. One of Cantor’s specialties, I’m obliged to tell you, was blackface. In fact, Cantor was the last major star to come of age wearing burnt cork at least part of the time. It was perhaps a sign of changing times that the character Cantor created was against stereotype however—he played a character who was kind of a bookish nerd, a sissy in glasses who went around using big words. In the sketch with Williams, he played Williams’ son, an educated young man who was appalled by the illiteracy of his father, a Pullman porter. Imagine the spectacle: one white guy in blackface and glasses, playing against a black man in blackface – by modern standards it’s almost as strange as it is offensive.

But as distant as that routine is to our sensibilities, a lot of the Follies comedy is quite familiar to us because we have literally seen it. WC Fields recycled just about all of his sketches from the teens and twenties into his movies. In addition to the billiards sketch, there was the golf sketch, a sketch where he’s trying to sleep on a hammock and keeps getting all these noisy interruptions, and a sketch where he takes his family out for a disastrous ride in a car. If you’ve seen It’s a Gift or Six of a Kind or You’re Telling Me you’ve seen snatches of stuff the Follies audiences saw.

Ziegfeld famously had a tin ear for comedy. He didn’t particularly like any of these comedians, and initially wanted to fire many of them. He was of course most interested in the spectacle of beautifully draped and undraped females, and the set and costume design that framed them like a beautiful setting frames a gem.

In 1919 his whole philosophy was put to music by Irving Berlin. One of the songs he wrote for the Follies that year “A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody” was to become the unofficial theme song for the Follies forever after. Song of course is another way vaudeville influenced the Follies. Berlin was perhaps vaudeville’s most successful and most prolific songwriter, penning tunes for the likes of Fanny Brice, Al Jolson, Belle Baker, Mae Irwin, and Polly Moran. It’s not surprising then that he also became the songwriter most associated with the Follies. Other songs Berlin wrote for that 1919 show included the Eddie Cantor novelty “You’d be Surprised” and “Mandy” which was the big finale sung by the entire cast. Other Berlin Follies songs over the years included “Blue Skies” performed by Belle Baker in 1926, and the entire score for the 1927 show, something which no single composer had previously been allowed to do on the Follies.

Berlin did not provide all of the Follies’ defining moments in song. One of the high points in the entire history of the Follies was Fanny Brice’s heart-rending rendition of the song “My Man” in 1921. “My Man” was actually a French hit refitted with English lyrics by the writer Channing Pollock. In the wake of Brice’s very public troubles with her gangster husband Nicky Arnstein, and the fact that the usually hilarious Brice was here in dead, tragic earnest, gave the song rare power and poignancy it mightn’t have otherwise achieved, and it became a sort of signature song for Brice.

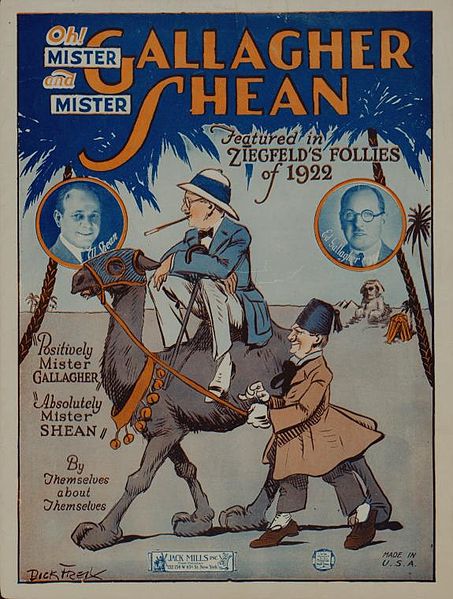

The following year, a very comical song was the hit of the Follies, then of vaudeville, and, because of the new recording industry, living rooms throughout the nation. The team of Gallagher and Shean performed the song that goes “Oh, Mr. Gallagher, Oh, Mr. Shean” –and over the decades it has become one of the most sung and parodied songs in history. You can even hear it on the internet, and here it is.

The 1927 show was said to be the last great Follies of the glory years. There was one last hurrah for Ziegfeld in 1931, but everyone said it was a shadow of the Follies in its heyday. But since that last great Follies in 1927 everything had gone wrong. The stock market crash had ruined Ziegfeld, had contributed to killing vaudeville and had seriously damaged Broadway. But also the mood of the country had changed. The Follies, like vaudeville, were of the Jazz age – they bespoke an era of opulence and optimism, a time when things are going so well you could fritter away an evening on diversion, silliness and, well, “Follies”. During the Depression there was precious little to celebrate or party about. People still liked to escape, but think of the Depression-era musical 42nd Street. Singing, dancing, comedy, and a starving chorus girl who faints from hunger. When I think of entertainment in the 30s I think of horror movies and gangster pictures or Orson Welles presenting War of the Worlds. You needed at least an element of darkness to be in tune with that era and I’m not sure Ziegfeld or his most famous product would have been capable of accommodating that. Vaudeville is often said to have died in 1932 when the last two-a-day played at the Palace. Interestingly, Ziegfeld died at the very same time.

The two had always been entwined. The Follies had plundered vaudeville for talent and borrowed much of its format. And the many posthumous editions of Ziegfeld’s Follies (and movies about Ziegfeld and same) kept a bit of the vaudeville tradition alive as late as 1957. By that time, television had taken over. I guess none of us will ever know – can only imagine – what a poor substitute TV is for a Ziegfeld era vaudeville revue.

To learn more about the roots of variety entertainment, including vaudeville impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, consult No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous, available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and wherever nutty books are sold.

[…] ago about the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra’s new record Midnight Frolic thinking the focus was Ziegfeld’s revues. Having received the CD in the mail, I discovered the subject of the album is more narrow, […]

LikeLike

[…] Orchestra is releasing this excellent looking album today. The Midnight Frolic was of course a Ziegfeld show – – it’s where folks like Eddie Cantor and Will Rogers got their start before […]

LikeLike

[…] Tree”. Starting in 1917, she’s in the chorus of big time revues like Miss 1917, and the Ziegfeld Follies of 1918, 1919 and 1920. It was Ziegfeld who changed her name to “Muriel”, the name under […]

LikeLike

[…] of the acts on view there was Eugene Sandow, Ziegfeld’s strongman. (The success of this exhibition was what led to the later more ambitious tour of his […]

LikeLike

[…] 1907 she hit it big at Proctor’s 5th Avenue theatre and appeared in the very first Ziegfeld Follies. In 1908 she married singer/piano player/composer Jack Norworth,her second husband of five. Bayes, […]

LikeLike

[…] nightclub the Diamond Horseshoe, which employed many ex-vaudevillians. In 1943, he purchased the Ziegfeld Theatre. And, his most important legacy of all, the Billy Rose collection at the New York Public […]

LikeLike

[…] loosely timed to some music. This was enough to bring her ravishing beauty to the attention of Flo Ziegfeld, who booked her for his 1917 Follies. This was the most successful edition of the Follies to date, […]

LikeLike

[…] rose to big time and revues: the Passing Show (1915), the Palace (1916), Hitchy Koo (1917), the Ziegfeld Follies of 1918, and the Greenwich Village Follies […]

LikeLike

[…] 1911, he came to New York, appearing in the Ziegfeld Follies that year. In this and the next follies he formed a sort of ad hoc comedy team with Bert Williams […]

LikeLike

[…] Wilhelm Muller, in 1867, in Koenigsberg, Prussia, Eugene (pronounced “oy-gun”) Sandow was Flo Ziegfeld’s first p.r. […]

LikeLike

[…] week for being too tall (he was 6’ 3”). After a brief stint as a soda jerk, he was cast in Ziegfeld-produced Eddie Cantor vehicle Whoopie (1927). When the show closed, Ebsen brought Vilma to New […]

LikeLike

[…] 1929, while still playing vaudeville and speakeasies, they were cast in their first book musical, Ziegfeld’s Show Girl. Their first film Roadhouse Nights was released in […]

LikeLike

[…] major black star in motion pictures, a series of one-reel silent shorts for Biograph. In 1911, Ziegfeld hired him for his Follies – the first black to be so honored. When most of the cast threatened to […]

LikeLike

[…] had. Prestige dates followed through the thirties: Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds in London (1936), The Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, and the Broadway show Babes in Arms (1937) where their choreographer was […]

LikeLike

[…] vaudeville had passed. They toured in various editions of George White’s Scandals and the Ziegfeld Follies. Later, Toy (whose real name was Margie) changed her name to Hoo Shee, and her brother […]

LikeLike

[…] was “Sadie Salome, Go Home”. She was a hit in The College Girls in 1910. She performed in the Ziegfeld Follies in 1910 and 1911. Like Jimmy Durante, she was one of the few to make it big in show business […]

LikeLike

[…] 125th Street, a common stage trick in those days. It was also how Al Jolson got his start. Ziegfeld hired Willie to do this bit for his show The Little Duchess but his voice started to change, and so […]

LikeLike

[…] the mid-teens he began to work in Broadway revues, starting with the Ziegfeld Follies in 1914. In the 1915 edition, there occurred one of the most notorious anecdotes in the […]

LikeLike

[…] team had great succes in vaudeville and in revues such as the 1917 Over the Top, Ziegfeld Follies, Earl Carroll’s Vanities, and The Greenwich Village Follies. In 1927 they recorded their […]

LikeLike

[…] debut was a 1927 job fronting Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra at the Paramount Theatre. In the 1927 Ziegfeld Follies she introduced another hit “Shaking the Blues Away”. The following year she appeared in […]

LikeLike

[…] to some of her more compliant coworkers. For example, she performed in the 1936 edition of the Ziegfeld Follies, as well as the Broadway shows Ali Baba Goes to Town (1937), and My Lucky Star (1938). In […]

LikeLike

[…] of all Where’s Charlie? (1948). Besides The Wizard of Oz, he can be seen in the films The Great Ziegfeld (1936), Rosalie (1937) Sweethearts (1938) April in Paris (1952) and one of many film versions of […]

LikeLike

[…] briefly had a number in the 1909 Ziegfeld Follies (a jungle number) but was cut out when Eva Tanguay replaced Nora Bayes as the star. It […]

LikeLike

[…] success. He had a difficult personality that kept getting in his way. He was fired from the 1925 Ziegfeld revue No Foolin’ for mouthing off to the boss. He blew a contract with Fox Pictures by refusing to […]

LikeLike

[…] next step was Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolics, his rooftop after-hours follow up to the Follies. Cantor was given a one-night […]

LikeLike

[…] 1917, he broke into Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolic, which he continued to play, along with the Follies, Earl Carol’s Vanities, and […]

LikeLike

[…] 1911, Ziegfeld booked them for the Follies, and in so doing created the personae and mystique that was to be the […]

LikeLike

[…] longevity followed throughout the 1940s. After having been passed over in favor of Bob Hope for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, Berle got to do the 1943 edition, which played 533 performances, longer than any […]

LikeLike

[…] she managed to get a Big Time agent named Frank Bohm who straightaway got her cast in the Ziegfeld show A Winsome Widow with Fanny Brice, the Dolly Sisters, and Leon Errol. She left the show after […]

LikeLike

[…] hours a night. In addition, Houdini was one of the greatest publicists ever, up there with Barnum, Ziegfeld and Billy Rose.Will Rogers called him “the greatest showman of our time by far”. No other […]

LikeLike

[…] the Barnum Museum, Makor (92nd Street Y), the Theater Museum, Eldridge Street Synagogue, the Ziegfeld Club, the Moisture Festival (Seattle), and numerous other […]

LikeLike

[…] he moved on to a two act with his first wife Betty. In 1923 he inked a five year contract with Ziegfeld to perform in the Follies. In 1926 Ziegfeld teamed him with Woolsey for the show Rio Rita. A 1929 […]

LikeLike

[…] year he debuted on the very first night of the very first season of Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolics. Because the same audience returned to this show every night, Rogers needed a […]

LikeLike

[…] 1915, he joined the Ziegfeld Follies where he worked straight through 1921. He performed in numerous other revues and book shows through […]

LikeLike

[…] Anna Held Today is Anna Held’s birthday, she of the famous milk baths. Before becoming Flo Ziegfeld’s second great entrepreneurial project (after strongman Eugene Sandow) the Polish-born Held was a […]

LikeLike