“Maybe you think you were handled roughly as a kid – watch the way they handle Buster!”

– a 1905 ad for The Three Keatons

Here’s something we haven’t seen in a while–a domestic abuse act! Many people today don’t know that the great silent comedy star Buster Keaton (whose birthday is today) started out as part of a family act with his parents, Joe and Myra. By the time he left the act to star in motion pictures with Fatty Arbuckle at age 22, he had already been doing slapstick comedy for over 86% of his life. He’d also conditioned himself to be nearly impervious to pain, out of sheer physical and psychological necessity.

Myra Keaton came from a show family. Her father Frank Cutler ran and performed in the Cutler Comedy Company, a traveling medicine showthat also featured melodramas, banjo music and blackface minstrelsy.** Little Myra (who stood 4’11” even in adulthood), played piano, coronet, bull fiddle and sax, and sang.

Joe Keaton got involved in the company when they passed through Oklahoma (then known as the Indian Territory). Joe was a character – a sort of cocky, bull-shitting drifter like Billy Bigelow in Carousel. The sort of man who relished a fight at the slightest perceived insult. Ed Wynn called him a “totally undisciplined Irish drunk”. Cutler hired Keaton as a sort of roustabout. Keaton attempted performing as well, but he was a big flop. It was clear to Cutler that Keaton’s primary interest in the company was Myra. Not interested in having such a worthless wastrel as a son-in-law, Cutler gave Keaton the axe. Keaton left the company but Cutler’s plan backfired. Myra ran away and married Keaton instead.

Several years of privation and hardship followed. Where life with the Cutler company was relatively comfortable and respectable, Joe and Myra were now shifting for themselves with far inferior medicine shows, just barely eking out a living.

While they were performing with the Mohawk Medicine Show in Piqua Kansas in 1895, Myra stopped to give birth to their first child, Joseph Frank Keaton. Legend has it that the baby literally had a steamer trunk for a crib. While performing with the California Concert Company, Joe and Myra became the best of friends with Bess and Harry Houdini. It was Houdini who supposedly nicknamed the child “Buster” when the precocious child fell headlong down several flights of steps, although this may be apocryphal (print the legend!).

In 1899, the family moved to New York City to break into vaudeville. By this time, they had evolved quite an act, developed in their years with the medicine shows. Called “The Man with the Table,” it involved Joe doing everything conceivable acrobatic that it is possible to do with a…table. He would dive onto it, do handsprings off it, fall from it onto his head. He might choose from a couple of different climaxes for the act. He might place a chair on top of the table, and from a standing position, leap so high into the air that he would land sitting in the chair (when he was sober enough to get it right). Another showstopper would have Myra sitting on top of the table, and Joe kicking her hat off her head. (The martial arts style high kick was Keaton’s specialty. He had developed the technique while brawling, and it was always his secret weapon in those situations. Keaton could kick up to eight feet high.) Meanwhile, while Keaton was doing all this kicking, falling and leaping, Myra would play her cornet, which was thought to give the act a little class.

Their first New York job was at Huber’s Museum, where their buddy Houdini had also gotten his start. It was only one week’s employment, and it’s a fortunate thing it was: at Huber’s you worked 15-20 shows a day – a grueling grind for anybody, but hell on an acrobat. After the Huber’s date, Joe unsuccessfully pounded the pavement for some time, before fortuitously bumping into Tony Pastor on the sidewalk. The fast-talking Keaton described his act to him, and landed a job. They did 3-4 shows a day during the engagement, and they were last on the bill.

The Keatons were now a vaudeville act. It remained only for Buster to get involved. His first onstage appearance was at age three, when he crawled and joined his parents uninvited, to gales of laughter from the audience. It wasn’t until Buster reached the age of five that he became a regular part of the act.

The Three Keatons’ act would play as shocking and as dark today as it no doubt did then. The gist of the routine was that Buster would torment Joe while he was busy doing something and then Joe would proceed to “discipline” him. “Father hates to be rough,” he’d say just before slinging his son around stage like a sack of turnips. Joe and Buster were dressed identically in very strange grotesque outfits. In a typical routine, Joe would come out and sing a song. Buster would enter from behind and carefully select a broom from 15 or so that were arrayed onstage and then, taking careful aim, crack Joe over the skull with it. In another bit, Joe is shaving at a mirror with a straight razor. Unseen by Joe, Buster begins to swing a basketball attached to a rubber house over his head, each pass getting closer and closer to Joe’s head until it finally smacks him. In response to these shenanigans, Joe “swings Buster around, bounces him off the scenery, throws him offstage”, and otherwise exercises his fatherly prerogative.

Nobody had ever seen anything like this before. It gave the act an edge, a gimmick that it had previously lacked, and the Three Keatons now became a big success. Offers flooded in. Though the Keatons were never major headliners, they were successful and constantly booked. They were very well known and had lots of fans. Will Rogers wrote of going to see them on his honeymoon – and preferring them to the Great Caruso.

The success of the act can be chalked up to two things. One: shock value—one could not believe what one was seeing. Two, and more importantly, Buster turned out to be a child prodigy, a sort of Mozart of physical comedy, with a gift for mimicry and improvisation that already outclassed most adults in the field. The critics raved about Buster.

James Austin Fynes, Proctor’s general manager was one of the first to spot Buster’s talent. He advised Joe and Myra to claim Buster was seven years old to help forestall the trouble with the authorities that was almost sure to come. At the turn of the century, they played Proctor’s Albany, where they did so well, they were moved three times to better spots during the run. In 1901, they played Proctor’s Pleasure Palace, truly the big time.

As time went on, the act got progressively rougher. A suitcase handle was sewn onto Buster’s back so he could be easily picked up and thrown. Keaton regularly chucked the little guy into the orchestra just for laughs. Like a cat, Buster needed to become adept at taking falls, relaxing and tumbling into them, or risk broken bones or worse. Joe even threw Buster at some hecklers once, advising him just before letting him go to “tighten up your asshole”. Buster came out okay, but he broke one of the young men’s noses. There was a Pavlovian quality to Buster’s training. He was not allowed to cry or laugh or else he’d get beaten. This is the origin of Keaton’s famous “stoneface”. Meanwhile, his father’s self-discipline was such that he once accidentally kicked the eight-year-old Buster in the head, rendering him unconscious for 18 hours.

It’s heartening to know that even in those less enlightened times, plenty of people were outraged (and many more, were at least uncomfortable) with this act. From the first, the Keatons were plagued by the attentions of the Gerry Society (the NY Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children). Gerry representatives would frequently come around to spy on the Keatons’ shows. The Keatons did everything they could to thwart them, right down to dressing Buster in a little suit, derby and cane so that he would seem like a midget.

Joe compounded his own woes by envisioning an Eddie Foy-like kiddie empire, involving Buster’s little brother Harry (known as “Jingles”) and baby sister Louise in the act. In 1907, Keaton trotted out the whole brood on stage for a benefit, and was nabbed but good by the Gerrys – banned from the New York stage for two years, when Buster would turn “16”. (Really 14, for the Keatons had been making Buster two years older). Without Buster, there could be no act; he was the one who got all the raves. Lacking Buster’s talent, Jingles and Louise were shipped off to boarding schools. A 1909 tour of England was a disaster, when the bookers and audiences there were appalled and offended by the child abuse. The Keatons sailed back to the US one week later. That year they got their revenge by staging their triumphant return to the New York stage at Hammerstein’s Victoria.

Joe revealed his business acumen (or lack thereof) by turning down an offer from William Randolph Hearst to portray Maggie and Jiggs in a series of silent comedies based on the comic strip Bringing Up Father. Joe had an irrational dislike of films…one which his son very shortly was to prove he did not share.

The act went progressively downhill from this point. As a teenager, Buster got bored and sloppy in the act. Joe’s drinking got worse and worse so that he could be reckless, mean and sloppy himself on stage. Buster, tired of absorbing his blows, started hitting his father back. By the time we reach the point of a twenty year old and his drunken father angrily trading fisticuffs onstage, we have strayed really far from the charms of the original act.

In 1916 Joe’s long simmering feud with Martin Beck came to a boil. Beck was the manager of the Palace as well as the Orpheum Circuit. He was notorious for his weekly meeting wherein he conferred with his staff like some Anti-Claus and decided who was naughty and who was nice (and consequently got work). Joe Keaton was never nice. The final nail in his coffin was an incident in Providence. Keaton, enraged by some cheap prop furniture procured by a stingy stage manager, proceeded to smash every stick of furniture in the theatre. It was just a matter of time before the Keatons were finished in Big Time.

A few days later, Beck was backstage when the Keatons were about to go on. “Make me laugh, Keaton” Beck is reported to have taunted. True to form, Keaton literally chased Beck out of the theatre and half way down the street. It’s a hot tempered vaudevillian indeed who tries to strike the most important booker in vaudeville.

Finished in big time, the Keatons started working the lowly Pantagescircuit, but it was hopeless. At this point, Joe was never NOT drunk. Buster and Myra quit the act, leaving Joe to sober up on his own.

The Keatons’ agent Max Hart (who was also an agent for Will Rogers,W.C. Fields, Bert Wheeler, and Eddie Cantor) booked Buster in The Passing Show of 1917. This was a very good booking indeed. Nevertheless, Buster dropped this prestige gig in favor of what was at the time a huge gamble: he opted to make films with Fatty Arbuckle instead.

After a brief apprenticeship with Arbuckle and a short stint in the army in World War I, Keaton went on to make 19 perfect shorts (1920-23) and 10 perfect features (1923-28) for his own company, Comique. Surreal, fast-paced and highly inventive, these films continue to inspire film-makers as diverse as Woody Allen and Steven Spielberg today. These highly personal films usually pitted Buster against impossibly overwhelming forces such as a tornado, a burst dam, or an avalanche of boulders, against which he emerged victorious through sheer offbeat ingenuity. Rare even then, Buster did all of his own stunts, accounting for many cheerfully broken bones over the years. Some of his films, like The Navigator were huge hits in their own day. Others, like The General were major flops that have over time come to be considered masterpieces. A marriage to Natalie Talmadge (whose sisters were both movie stars, and whose brother in-law Nicholas Schenk was a major mogul) assured Keaton status as part of Hollywood’s royalty throughout the 1920s.

In 1928, he became a contract player for MGM, and after a couple of great silent films (The Cameraman and Spite Marriage), he began a long and painful path to almost total self-destruction.

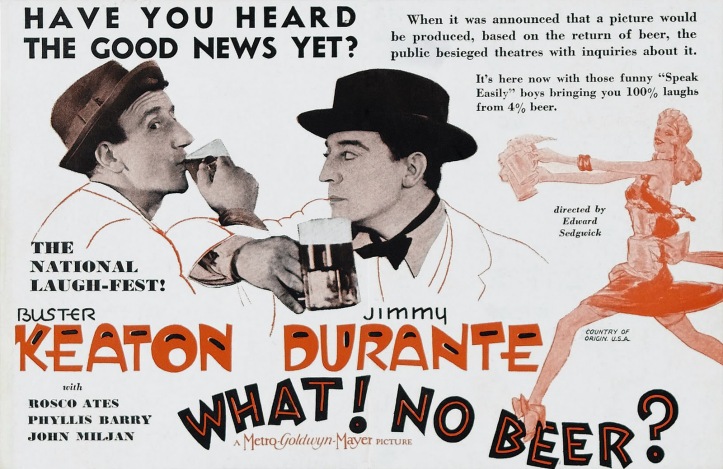

His decline may be attributed to several factors. First, oddly enough, his voice. Although he had a great one, it worked against the type of characters he usually played. His character was usually a young man, a wispy, and lovelorn character. He was often cast as a sort of wealthy naif, a young New York playboy pampered by butlers and the like. The image contrasted sharply with his squeaky, raspy voice, which was naturally deep and hardened from years of smoking and drinking. This, combined with his rustic Kansas accent, undermined the romantic leading man idea. Keaton had the voice of an old sailor – the voice of experience, a character who goes to bars and visits prostitutes. If he’d begun playing farmers – farmers with crazy inventions out back in the barn – his voice would have worked in talkies. Second, MGM tampered with his character. In Keaton’s third wife Eleanor’s words, previously, “he had never been a bumbler.” Instead of creating chaos wherever he went, Buster’s character always tried to impose order on a universe that was chaotic. Now the studio increasingly cast him as an incompetent, the sort of part that did not jibe with his natural dignity. Furthermore, for his last three features he was teamed with Jimmy Durante, no shrinking violet, who couldn’t help but hog every scene he was in, while Keaton floundered in uncertain seas.

Despite all this, Keaton’s MGM talkies, though nearly unwatchable today, were big hits at the time. In them we see sad evidence of the third and most crucial factor in Keaton’s rapid decline in the early thirties: he’d inherited his father’s alcohol problem. Each Keaton performance is progressively more unbearable, as his liquor problem grows to the point where it was visible onscreen. The problem was exacerbated by his divorce from Talmadge in 1932. By then Keaton drank so much he either missed workdays or would be drunk for the shooting. L.B. Mayer fired him, but Irving Thalberg pleaded with him to come back. Buster, brazenly assuming there would be offers from other studios, turned Thalberg down. The other offers never materialized.

From here, Keaton tumbled to poverty row, first with a series of two-reelers for Educational Pictures (1933-37) (some of which are quite good), then some Columbia shorts directed by Jules White of Three Stooges fame. The 1940s were his toughest decade, when he worked primarily as “technical advisor” for MGM films, including many by Red Skelton. A highly successful 1947 performance at Cirque Medrano in Paris helped rehabilitate his reputation, as did some 1949 shots on The Ed Wynn Show. In 1950, he had his own Buster Keaton Show on a local Los Angeles station, then went on to a series of much cherished guest shots in films and television over the next 17 years. Keaton worked on prestige TV programs such as Playhouse 90 and The Twilight Zone, as well as numerous commercials. Films beckoned one again, too. High profile cameos in Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight (1952) and Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950)brought him back to cinemas, although in both these films his scenes had an eerie, unearthly quality, as though he were some sort sort of ghost from the early days of flickers. In the sixties he was a familiar face in the Frankie Avalon-Annette Funicello beach party movies – something akin to hiring Heifitz to play third fiddle at a barn dance. If the beach party movies weren’t proof enough that he’d take whatever work he could get, in 1964 Keaton starred in an art film called Film by Samuel Beckett, where he was directed to stumble around bumping into walls with a sack over his head.

One of his last projects turned out to be the very last one for his co-star Ernie Kovacs, a TV sit-com called The Medicine Man. It featured Keaton as the Indian sidekick to Kovacs’ travelling snake-oil salesman. Keaton had come full circle to his medicine show origins. He passed away in 1966

In addition to the dozens of films Keaton made himself, there are two bio-pics for the intrepid investigator to explore. The 1956 film The Buster Keaton Story is terrible. Much more interesting and accessible is a 1969 film called The Comic starring Dick Van Dyke and directed by Carl Reiner. The film is clearly based on Keaton’s life (among others).

Read 50 more posts about Buster Keaton here.

To learn more about silent and slapstick comedy films, including those of Buster Keaton, don’t miss my book Chain of Fools: Silent Comedy and Its Legacies from Nickelodeons to Youtube, just released by Bear Manor Media, also available from amazon.com etc etc etc To learn more about vaudeville and acts like The Three Keatons, consult No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous, available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and wherever nutty books are sold.

**Obligatory Disclaimer: It is the official position of this blog that Caucasians-in-Blackface is NEVER okay. It was bad then, and it’s bad now. We occasionally show images depicting the practice, or refer to it in our writing, because it is necessary to tell the story of American show business, which like the history of humanity, is a mix of good and bad.

[…] by Andrew Speno | posted in: Hollywood and Vaudeville | 0 The Three Keatons […]

LikeLike

[…] and he also became the circus ring master. He went on tour in America and shared the bill with The Three Keatons, one of which was the famous Buster Keaton, who was famous as an actor, a comedian, a film […]

LikeLike

[…] an extended scene with his dad Joe that probably is reminiscent of the family’s old “Three Keatons” […]

LikeLike

[…] business partner in am medicine show) taught him some magic tricks, and his family’s act, The Three Keatons, taught him about comedy and how to take a fall, which lead him to becoming the world’s […]

LikeLike

[…] It’s a depressing arc, and Bree plays it that way, her somber face only slightly less stony than Buster Keaton’s as she mirthlessly essays a number of mostly obscure, pre-Jazz era showtunes in her little patchwork […]

LikeLike

[…] play adaptation of the comic strip The Katzenjammer Kids. Her mother was also an actress. As with Buster Keaton, its rumored that Joan’s cradle was literally a steamer trunk. She made her stage debut in her […]

LikeLike

[…] * Vaudeville programs from as early as 1898 (on one ad, he shares a bill with the Three Keatons) […]

LikeLike

[…] trying to copy Laurel and Hardy in some respects, but I also spotted bits lifted from Lloyd, Keaton and Chaplin. The film was directed by Del Lord of Three Stooges fame. Very […]

LikeLike

[…] afficianado, the jaded film fan such as myself who has long since seen the major movies of Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd etc a long, long time ago, and now must go farther out on the proverbial ledge for new […]

LikeLike

[…] had dried up, so they moved to Hollywood. Her first break was in a Mack Sennett picture with Myra Keaton and the Sons of the Pioneers. She continue to make films for the next 20 years or so, with Abbott […]

LikeLike

[…] funniest movies ever made. But there is nothing in the team’s canon to equal the best of Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Langdon, the Marx Bros, or Fields as […]

LikeLike

[…] Time vaudeville. Will Rogers called it “the greatest vaudeville theatre of that and all time.” Buster Keaton praised the Victoria as “vaudeville at its all time […]

LikeLike

[…] slightly larger than Bazooka Joe Comics. To be more accurate, it’s like that newspaper that Buster Keaton keeps opening up in The High Sign, until it is roughly the size of a bed sheet. The broadsheet […]

LikeLike

[…] one more American film, the 1952 Limelight which revisited his music hall origins, and co-starred Buster Keaton, but unfortunately dwelt again on the issues of death and suicide. Having recently married the […]

LikeLike

[…] gave him his own company at Metro, the Comique Film Company, where his supporting players were Buster Keaton and Arbuckle’s nephew Al St. John. In 1920, Arbuckle left to make features, bequeathing Comique […]

LikeLike

[…] bearing the name The Ed Wynn Show debuted on local a Los Angeles station. (This is the show where Buster Keaton’s comeback is said to have began). Wynn then worked as one of four rotating hosts of NBC’s Four […]

LikeLike

[…] officers) who relished making life hell for “uppity” Negroes. A touching anecdote has Joe Keaton finding himself sitting at the same bar with Williams and noticing that they are opposite ends. […]

LikeLike

[…] “There was no family act even remotely like it,” Foy said. Sure, there were four Cohans and three Keatons, but there was no act with eight family members (including Eddie; nine , including Mrs. Foy, who […]

LikeLike

[…] from his natural talent and grace, Chaplin owed his superiority as a slapstick film clown (with Keaton his only serious rival) to his training with Karno. Chaplin also appropriated many Karno gags and […]

LikeLike

[…] Harry regurgitation. In 1897 they worked Doc Hill’s California Concert Co, where they got to know The Three Keatons. Harry did seances and performed “second sight”. Here he perfected many of his Davenportesque […]

LikeLike

[…] and dance team Durbin and Hope that performed in a revue starring filmdom’s disgraced expatriate Fatty Arbuckle in 1924. When Durbin died of TB, Hope teamed up with another hoofer named George Byrne. Among their […]

LikeLike

[…] resorted to billing himself as “Al Jolson’s Brother” to get bookings. It was just as well – Buster Keaton claimed that he was the only blackface act he’d ever seen with a Yiddish […]

LikeLike