This author’s first exposure to Milton Berle was in the 1970s, when he was principally one of a seemingly limitless crop of septigenarian, cigar-smoking comedians that still dominated television at that time. The disparity between Berle’s legend and the codger I saw onscreen had me scratching my head for years. THIS was Mr. Television? This dirty old man who was constantly apologizing for his Joe Miller-style jokes was once such a phenomenon that he quadrupled the sale of tv sets? Restaurants emptied out on Tuesdays because of this man?

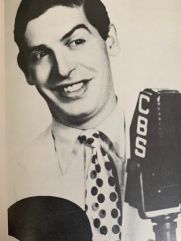

The mystery was cleared up when I finally got around to actually watching kinescopes of his old shows, The Texaco Star Theatre. The answer is, that middle-aged Berle (as opposed to the elderly Berle) was a ball of fire. The man had so much energy, and was given to such crazy spontaneity that it seemed as though he would jump out of the tv screen. Hilarious, kinetic and uninhibited – the sort of comedian who would run into the audience, snatch a woman’s furcoat out of her hands, and put it on. It seems like ancient history to see Berle so young. And yet, at that point, Berle had already been in show business for over 40 years.

“My childhood ended at the age of 5, ” Berle said in his autobiography, but, in some ways, his childhood extended well into his middle age. He started out as a child performer; his domineering stage mother Sarah (a.k.a Sadie) was one to rival Ma Janis and the Mother of the Hovics. Sadie would be looking over Milton’s shoulder well into his reign as Mr. Television.

He was born Milton Berlinger in 1908. Berle started his show business career out strong by winning one of the ubiquitous Charlie Chaplin contests in the mid-teens. A little-known fact is that he soon had a silent film career himself, acting as a child extra in some of the major releases of the time, including the comedies of John Bunny and Flora Finch, and films with Mary Pickford . Some of the films he was in were classics, such as the Mark of Zorro, and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.

In the teens, he worked with kids acts like that of E.W. Wolf, one of countless Gus Edwards imitators. He worked principally in the Philadelphia area, to avoid New York’s greater scrutiny by the Gerry Society. In the act he did his first sketch comedy and worked up an Eddie Cantor impression that was to be one of his staples for many years. His mother, who was not only pushy, but also sort of crazy and desperate, finagled him into Cantor’s dressing room once and forced him to do the impression. Cantor’s response was reportedly something like “that’s good, kid. So long.” Even more brazenly, she bullied their way past a stage manager at the Wintergarden and pushed Milton onstage during a Jolson performance. Through gritted teeth, Jolson permitted the obviously insane boy to do his Jolie impression and then dismissed him, all to the hearty amusement of the audience. Most perversely, when Milton was cast in a prominent revival of Floradora she made him start off his dance number on the wrong foot on opening night, screwing up the routine. She said it would get him “attention.” With attention like that, what’s so bad about obscurity?

In 1921, he teamed up with Elizabeth Kennedy, a talented Irish girl from Brooklyn. It was at this point that he changed his name to Berle, so that it would go better with Kennedy.Called “Broadway Bound”, their sketch was set in David Belasco’s office. Kennedy and Berle played kids who came to audition for Belasco, but, finding the office empty, while away their time demonstrating their talents. Berle did his Eddie Cantor impression. Kennedy did a Fanny Brice impression. Together, they did the Romeo and Juliet balcony scene. The act was very successful. After only a week, they were booked in slot number six at the Palace. More usually there were on third, so the could leave by 9:05 and satisfy the busybodies at the Gerry Society. They worked the Keith circuit for the next two years, until Berle got too tall, outgrowing the act.

Adolescence for performers is not only an awkward time, but strange. Berle’s mother demonstrated her eccentricity yet again by picking up girls for him. She’d sit the in the audience and strike up conversations with girls in their twenties, then bring them backstage to meet Milton, who was still a teenager. Then she would leave them alone. Berle’s theory was that this was her way of providing for an inevitable need of his while keeping him out of trouble. At the same time, she let him pal around with fellow kid performer Phil Silvers because “he’s a good boy”. Silvers brought him to meet his first prostitute.

No longer a “child” and not yet an adult, he struggled through the mid-1920s to find himself as a performer. He debuted as a single in 1924, singing, dancing, telling jokes, doing impressions, card tricks and even dabbling in drag. Whereas Kennedy and Berle were strictly big time Berle the solo had to go back to the small and work his back up.

By the late 20s, he was “Milton Berle, the Wayward Youth” and was quite a success. He’d discovered that supreme necessity of the vaudevillian: personality. For Berle, the gags may be hoary and stale, but a good comic could get over on the strength of his verve alone. He developed a brash quality that one associates with burlesque, although he never worked the girlie shows. He’d pick on people in the audience, ad lib, and get as close to risqué as he could without actually crossing the line. Berle later said he secretly patterned his walk, talk, tempo and flippancy on Ted Healy, one of his idols. When, late in its life, vaudeville evolved the role of master of ceremonies to helm the proceedings, Berle was one of the few naturally prepared to take on the job.

By the turn of the new decade, big things started coming his way. He did Rudy Vallee’s radio show. He did a Vitaphone short called Gags to Riches. Presciently, he did a closed circuit TV experiment with Trixie Frigenza. In 1932, he got an opportunity to m.c. at the Palace, when Benny Rubin came down with appendicitis. He was a smash hit, staying on eight weeks. He had a similar gig at the Chicago Palace the following year. It was around this time that Walter Winchell, by now a columnist, famously dubbed him “the Thief of Bad Gags”.

From here, Berle rapidly moved up into Broadway, radio, film and TV. Throughout, he took lucrative work in night clubs as vaudeville began to phase out.

He was featured in the 1932 edition of Earl Carroll’s Vanities, and subbed for Bert Lahr in the 1934 road tour of Life Begins at 8:40. In 1936, he did his first radio show the Gilette Original Community Sing. His first film was New Faces of 1937, and that year he also did one called Radio City Revels. Numerous films of comparable longevity followed throughout the 1940s. After having been passed over in favor of Bob Hope for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, Berle got to do the 1943 edition, which played 533 performances, longer than any other edition of the Follies.

Various radio formats were tried, with names like The Milton Berle Show, Let Yourself Go, Kiss and Make Up, and the Philip Morris Playhouse, before hitting the g spot in 1948 with the Texaco Star Theatre. In the following year, he did both a tv and a radio version of the show simultaneously, as well as a semi-autobiographical film called Always Leave Them Laughing. In 1950 the radio component was dropped, for, by that time, he was already Mr. Television.

His success was on such a scale that he and NBC optimistically signed a 30 year contract. Unfortunately, the party only lasted until 1955. by that time, Berle – and the audience’s attention span – were exhausted. They gave it another shot in the 1958-59 season with Kraft Music Hall but it didn’t strike a chord. His last show (of his original stretch) was Jackpot Bowling (1960-61), although he tried a comeback show on ABC in 1966, which folded after one season. Oh, how the mighty had fallen!

His film and tv career was for the next forty years a history of cameos and guest shots.

In night clubs, of course, he was still king. And he cast a long shadow. One would have to include Henny Youngman, Alan King, Jan Murray, and many, many others as acolytes in the cult of Berle. And he continued to hold court at the Friar’s Club in New York right up until his death in 2002.

We reluctantly end on a topic that is rightfully more the domain of burlesque than vaudeville: Milton Berle’s reputedly epic schlong. We resisted including it in this post for many years, but sadly it seems to be the aspect of Milton Berle that most contemporary people are curious about. His fellow comedians, many of whom apparently caught a glimpse of it at the pissoir, frequently joked about its enormous size, something they’d have been unlikely to volunteer doing if there weren’t some truth to the legend. Berle was married four times to three women, and by his own account, had affairs with Marilyn Monroe, Betty Hutton, and — most peculiarly, evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. At any rate, people seem obsessed by the subject of Milton Berle’s dong. Just google it — you’ll find an unconscionable number of articles devoted solely to that topic! But I think we can all agree that wang-size should be rated more an endowment than an accomplishment. It appears he had plenty of both to his credit.

To find out more about the history of vaudeville including the great Milton Berle, consult No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous, available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and wherever nutty books are sold.

[…] Blue (born this day in Montreal in 1901) got his start just like Milton Berle and Bob Hope — by winning a Charlie Chaplin impersonation contest. He was a drummer in comedy […]

LikeLike

[…] known for. This led to voice work on the top comedy shows of the radio era, Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Burns and Allen, Eddie Cantor, and many others. He became part of Olsen and Johnson’s crazy […]

LikeLike

[…] childhood ended at the age of 5, ” Milton Berle said in his autobiography, but, in some ways, his childhood extended well into his middle age. He […]

LikeLike

[…] nailed them ALL. In some respects, he was like Chaplin, Lou Jacobs, Bob Hope, Fred Allen, and Milton Berle all rolled into one. Except…well, he was pretty […]

LikeLike

[…] line could have (and most assuredly did) come out of the mouths of the likes of Milton Berle and Henny Youngman again and again for the remainder of the […]

LikeLike

[…] “comc laureates”, almost branches of the U.S. government. As opposed to the more burlesquey Milton Berle-Henny Youngman-Rodney Dangerfield approach, these are not men who take or deliver a pie in the […]

LikeLike

[…] be sneered at) he was an excellent straight man. He worked in the latter capacity, for example for Milton Berle at Proctor’s Newark. During these years of struggle, he became good friends with Burns and Allen. […]

LikeLike

[…] studio before the final credit crawl. In the 1954-55 season, he took over Texaco Star Theatre for Milton Berle (alternating with Donald O’Connor), and the following season, he had his own show The Jimmy […]

LikeLike

[…] if to prove every prejudice about vaudeville, backstage at the Palace Milton Berle once placed his hand on Ethel Barrymore’s ass. In his autobiography, he claims it was an […]

LikeLike

[…] as good therefore as four acts in one, combining the appeal of Charlie Chaplin, Weber & Fields, Milton Berle and, well, Zeppo, all in one act. W.C. Fields called them “the one act I could never […]

LikeLike

[…] a hack? After all, didn’t Jack Benny already play a violin badly for laughs? Didn’t Milton Berle already fire off an encyclopedia’s-worth of corny one-liners? Let’s just say Henny was […]

LikeLike

[…] British but could be as undignified, fun-loving and insane as the lowest of low comedians, such as Milton Berle and Bert Lahr, both of whom she worked with. A good example of this ability was her favorite stunt […]

LikeLike

[…] later claimed that it was an accidental response to the pain caused by an ingrown toenail – but Milton Berle claimed that Blossom Seeley was using the move as much as a year earlier for dramatic effect. Seems […]

LikeLike